The journalist Virginia Minaya interviews the artist ahead of her exhibition Mercedes en el Museo Sacro. Obras Recientes de Mercedes Pardo (August 11–September 15, 1996) held in Caracas at Galeria del Sacro. She is here presented as a pioneer of lyrical (non-geometric) abstraction in Venezuela, although her production spans beyond lyrical abstraction—some of her work can be considered hard-edge. While the article does not offer detail on the exhibition, the conversation makes an important contribution to the literature on the Venezuelan creator for the ways in which Mercedes Pardo (1921–2005) describes her own creative process. She explains her preference for large-scale artworks, and her focus on “the problem of painting as a language.” Pardo argues that her creative process starts with emphasis on the preparatory works and time to “ripen.” The question is: How do her creative rhythms and timelines not comply with the expectations of commercial galleries? According to her, her art is not quantitatively comparable to other artists because of the lengthy preparatory stages, moreover, her predilection for unique pieces as opposed to multiples. This is in line with her critique of the commodification of art and the invasive role or art dealers.

Another important insight is offered by her association of music and art, a constant search for “harmonious chords.” Music has historically been associated to abstraction, especially at the beginning of the twentieth century, because of abstract art and its ability to elicit emotions and reflections beyond reality; such a link became common among Venezuelan artists due to the works by Alejandro Otero (1921–1990) and/or Jesús Rafael Soto (1923–2005). Pardo also mentions how her work is perceived and understood by each viewer in their own individual ways. Her attention to the agency of each spectator’s sensitivity is positioned in the broader discourse of Venezuelan modernism, where artists saw the necessity of a revaluation of art, no longer as an anecdote, but an experience encompassing viewers. Indeed, this interview is eliciting remarks that are not otherwise easily found in Pardo’s literature, her views on the impact of colonization on Venezuelan culture among them. According to her, it made her countrymen forget how to use their hands, something inelegant and unfit for the higher classes.

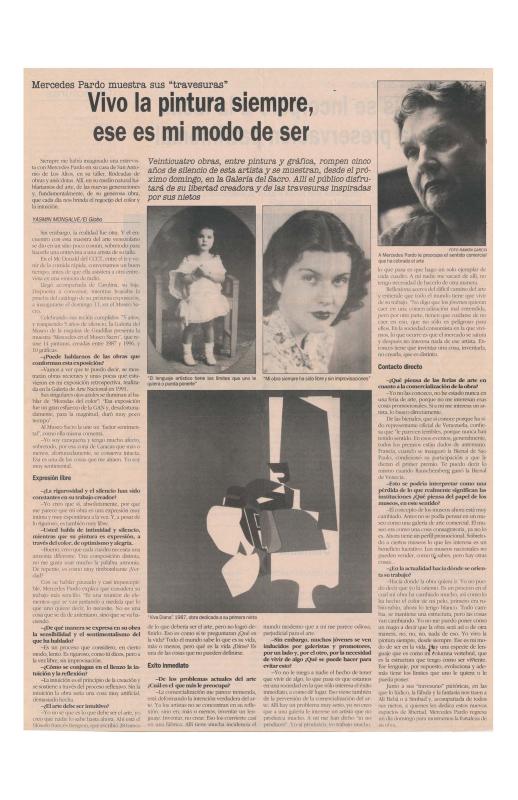

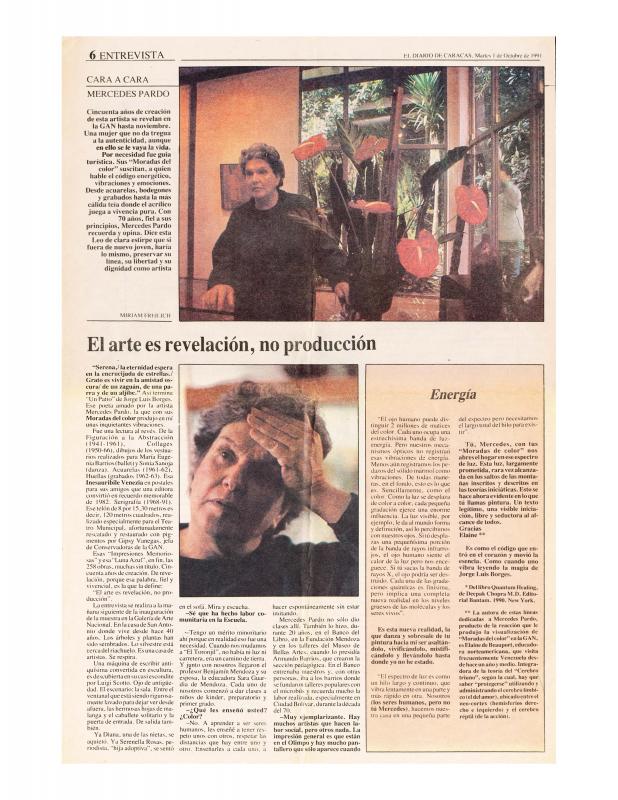

[For other articles on the Museo Sacro exhibition, see in the ICAA Digital Archive: Gustavo Jaén, “El azul y más allá” (doc. no. 1331004); Yasmin Monsalve, “Vivo la pintura siempre, ese es mi modo de ser” (doc. no. 1331036">1331036); and Anonymous, “Temor y temblor en busca de una íntima trascendencia” (doc. no. 1331053). For further reading on Pardo’s views on the commodification of art, see both Monsalve, “Vivo la pintura siempre, ese es mi modo de ser” (doc. no. 1331036">1331036) and Miriam Freilich, “El arte es revelación, no producción” (doc. no. 1325266).]