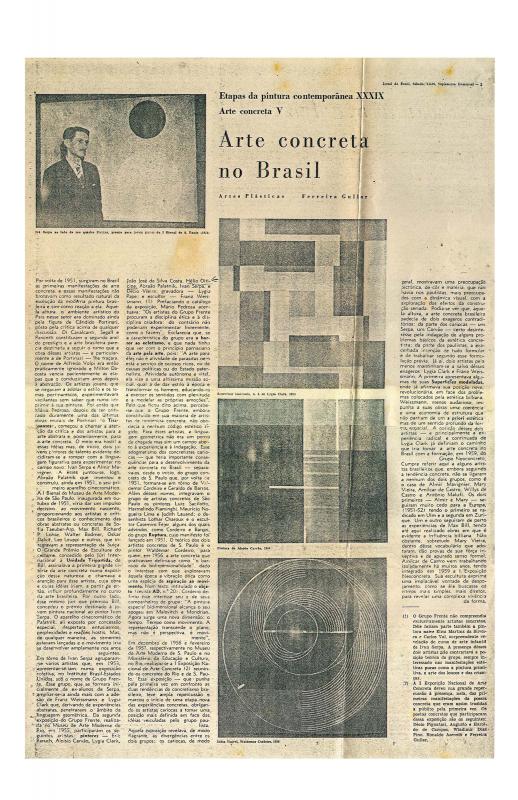

According to the author, the sculptor was already exploring Concrete art in 1952. Seven years later, at the I Exposição Neoconcreta (Rio de Janeiro), he reengaged with his “significative language,” which was based on sculpture. The constant element in his work was a single metal sheet that was folded in various ways, bent and twisted to create a sense of energy, forming unusual vectors whose forces seem to converge inward. The vitality and momentum of de Castro’s dynamic shapes appear to defy critical assessment, as if the underlying proposal were declaring, “the work is where the work is placed.” There is a tension that makes concrete rationalism seem metaphysical; it is matter in search of its abstract form, which is always earthly, always telluric.

Amílcar de Castro (b. 1920; d. 2002) was a well-known Brazilian sculptor. He studied drawing and painting with Alberto da Veiga Guinard in Belo Horizonte (MG). In the late 1950s—when he was the distinguished designer of the graphic renewal advocated by the Jornal do Brasil—he embraced the "Manifesto Neoconcreto" (1959). A year later he took part in the International Exhibition of Contemporary Art in Zurich, Switzerland. In the 1960s he was a regular exhibitor at the Salão Nacional de Arte Moderna (Rio); at its fifteenth edition he was awarded a grant to study in the United States, and settled in New Jersey, in 1968, on a Guggenheim grant. In 1977 he won the Prize for Drawing at the Panorama da Arte Atual Brasileira (São Paulo).

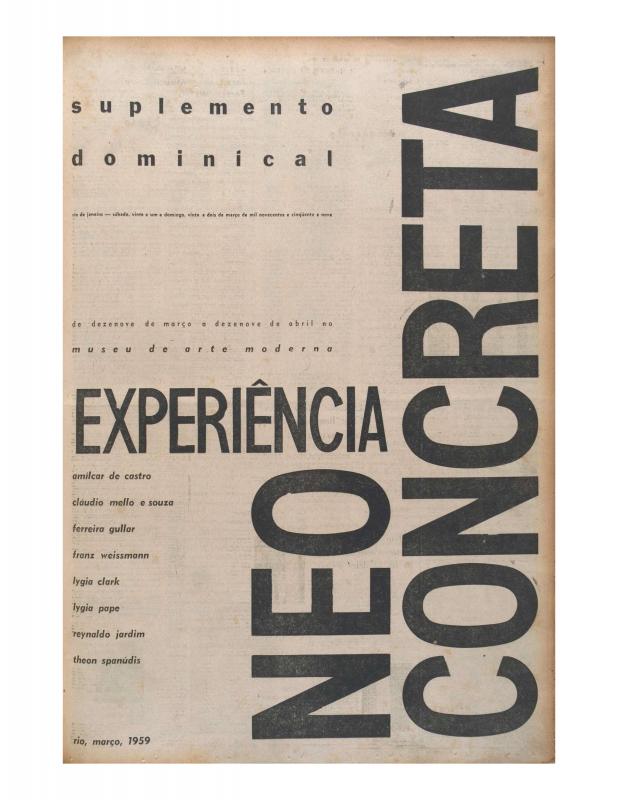

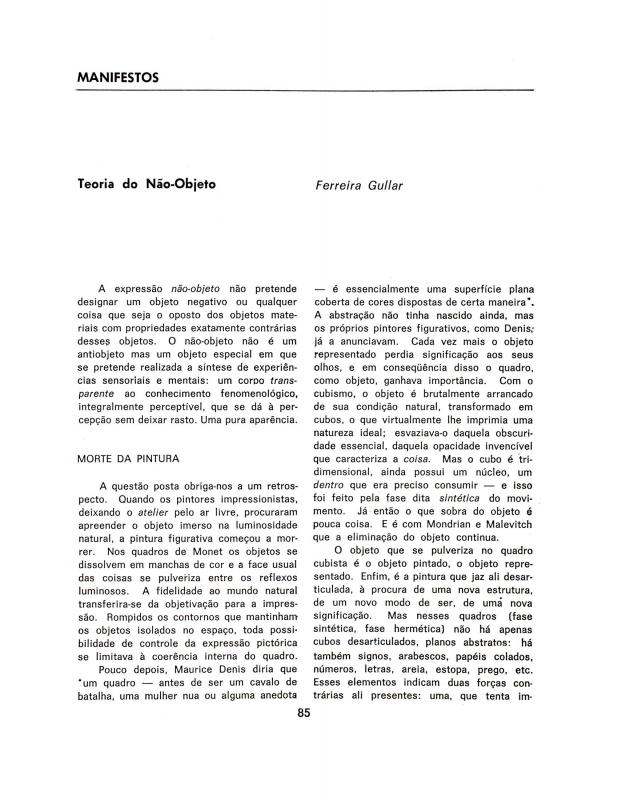

The critic and poet (José Ribamar) Ferreira Gullar (b. 1930; d. 2017), one of the Grupo Frente’s key theorists, published his first articles in the Sunday supplement of the Jornal do Brasil in 1955. He took part in the Exposição Nacional de Arte (doc. no. 1090217), at the Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo in 1956 and at the MES (Ministério da Educação e Saúde, the Ministry of Education and Health, which organized the Salão Nacional de Arte Moderna) in 1957. In response to the 1a Exposição neoconcreta in Rio de Janeiro in 1959, he wrote the "Manifiesto Neoconcreto" (doc. no. 1110328), which was also published in the Sunday supplement of the Jornal do Brasil. That same year he wrote “Teoria do Não-Objeto” (Theory of the Non-Object) (doc. no. 1091374), which was published in the same newspaper. From March 1959 to October 1960, Gullar published a number of theoretical articles: “Etapas da Arte Contemporânea” (doc. no. 1090830), which were later included in the book Ferreira Gullar: Etapas da arte contemporânea—do cubismo à arte neoconcreta (Ferreira Gullar: Stages of Contemporary Art—from Cubism to Neo-Concrete Art, 1998).

At that time, the name of the Galería Raquel Arnaud included the surname of her then-husband, the Argentinean filmmaker Héctor Babenco.