In this text, eminent Peruvian avant-garde poet César Vallejo remarks on André Breton’s “Second Manifesto of Surrealism” published in issue XII of La Révolution Surréaliste. [For additional information, see in the ICAA digital archive these related texts: José Carlos Mariátegui’s “Figuras y aspectos de la vida mundial: El Segundo manifiesto del suprarrealismo (1)” (doc. no. 1293556), and “Figuras y aspectos de la vida mundial: El balance del suprarrealismo. A propósito del último manifiesto de André Breton” (doc. no. 1293479)].

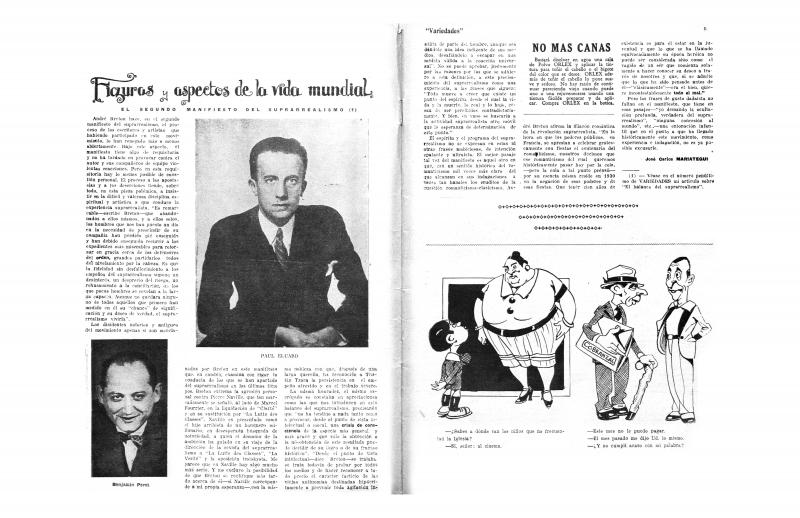

Published in the twelfth issue of La Révolution Surréaliste (December 1929), the second surrealist manifesto that André Breton wrote aimed to shed light on the political implications of that movement and to justify the expulsion of a number of its former members. Just a few months later, Breton’s polemic manifesto was discussed in articles by José Carlos Mariátegui, founder of the Partido Socialista Peruano (PSP), and by poet César Vallejo, a member of that party. An intellectual, Mariátegui, who returned to Peru from Europe in 1923, followed European politics and culture closely; he was well informed about European avant-garde movements, of which he considered Surrealism the most important because it was the only one that had embraced the Marxist agenda of proletarian revolution. Indeed, Mariátegui placed emphasis on the role that the “crisis of consciousness” advocated by Breton could play in the search for a new social order. Significantly, Mariátegui rejected the “épatante intention” of a number of phrases in the manifesto because, in his view, they were geared solely to the bourgeoisie and went beyond political doctrine to advocate release from all the tethers of reason. Notwithstanding, Mariátegui mostly praised the figure of Breton, whereas César Vallejo attacked him in “Autopsia del suprerrealismo,” an article submitted from Paris shortly after Mariátegui’s text appeared. In his article, Vallejo sharply questioned the Surrealists’ commitment to Marxism; he deemed them steeped in a nihilism that ran counter to affirmative Communist doctrine and condemned a formulaic avant-garde caught up in “literary schools.” Indeed, Vallejo’s demand that intellectuals commit to the proletarian revolution reflected a hardening of his stance after two trips to Russia, in 1928 and 1929 respectively.