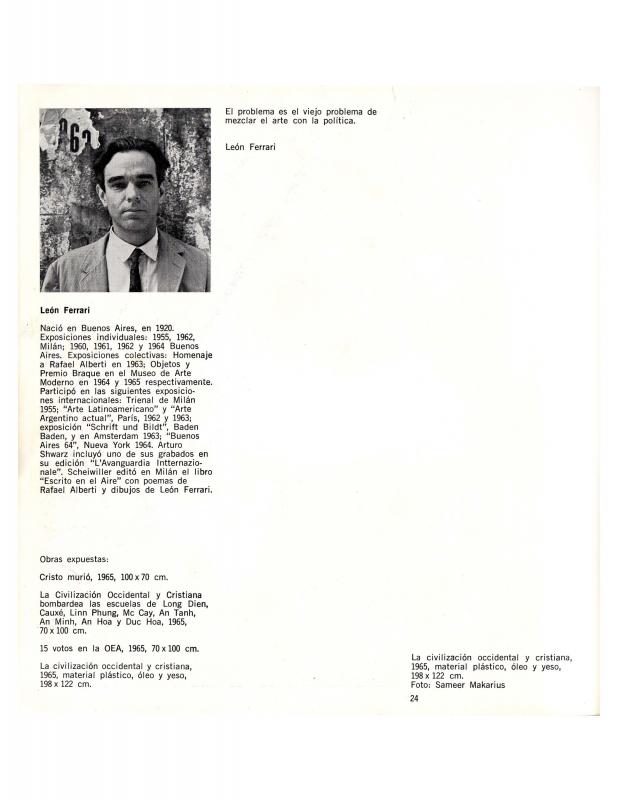

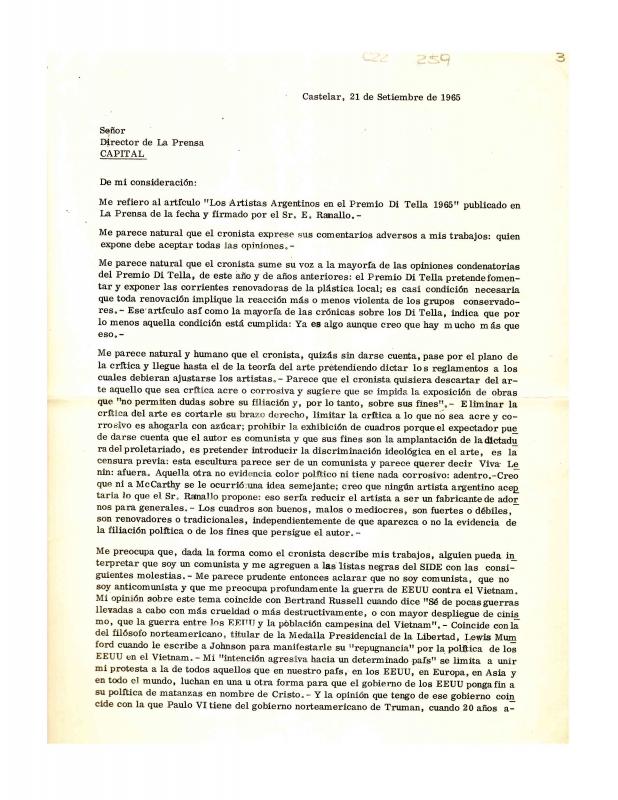

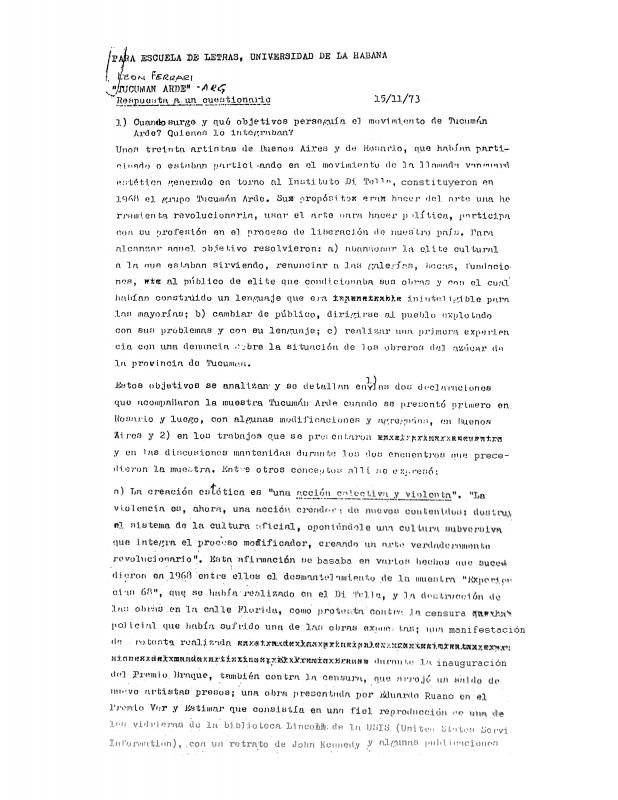

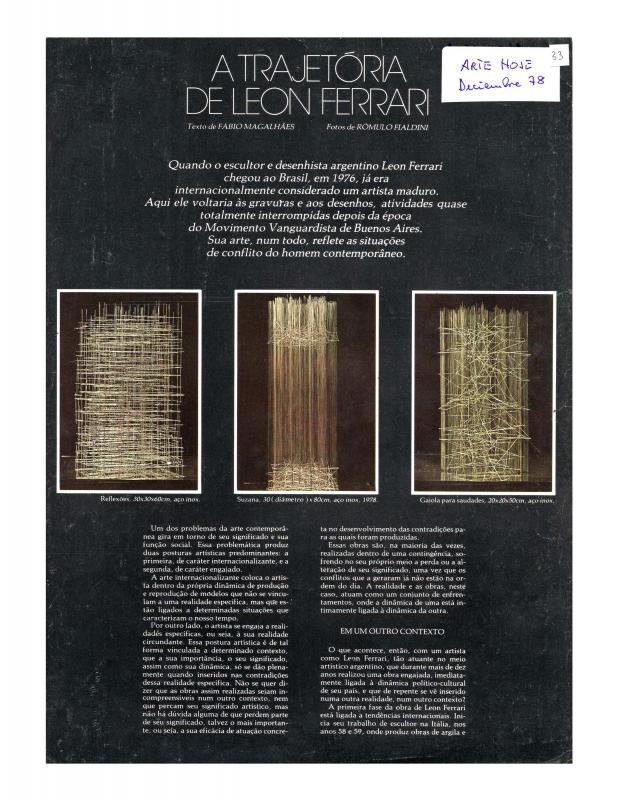

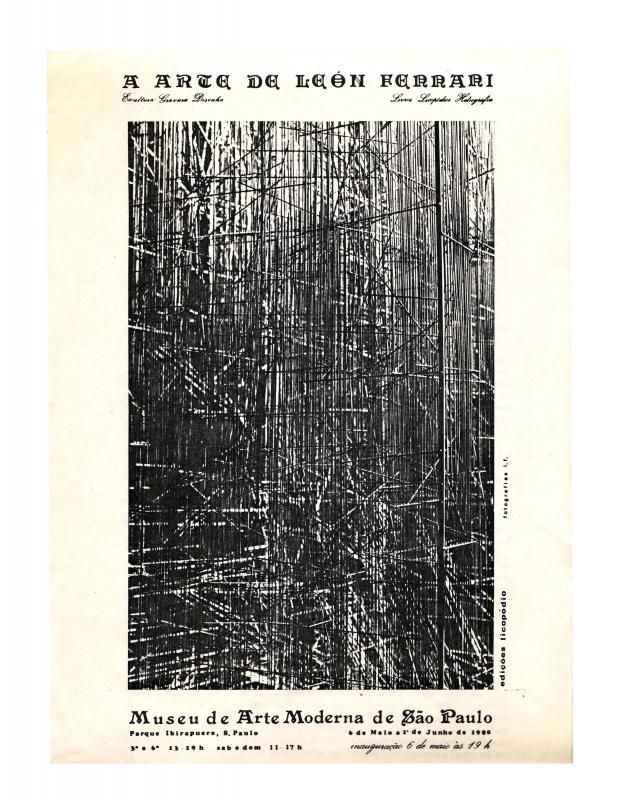

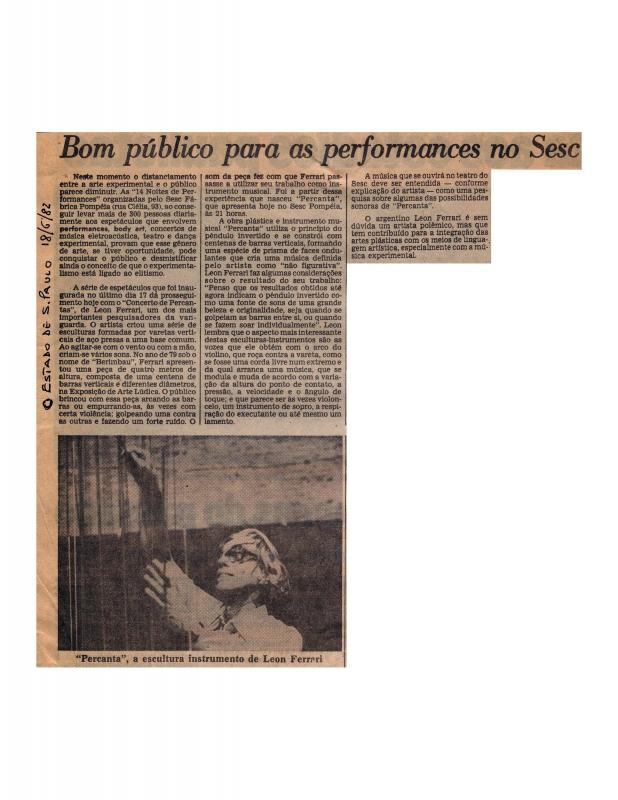

León Ferrari was born in Buenos Aires in 1920, the son of Augusto Cesare Ferrari, the Italian artist and architect. The younger Ferrari was a latecomer to the plastic arts, a status which allowed him to function as a link between the generation of artists from the late fifties and the young avant-garde of the sixties. His early works were ceramic sculptures, but in later years he experimented with wire structures, with a visual form of writing, and with collages. There are two distinct themes running through his work: one is a strong condemnation of military dictatorships, American imperialism, and the ideology of the Catholic Church. The other has a more formalistic quality, expressed in a conceptual style and, at times, in the surrealist tradition. His 1965 object-montage, titled Civilización Occidental y Cristiana [Western Christian Civilization], was censured at the Centro de Artes Visuales del Instituto Torcuato Di Tella [the Torcuato Di Tella Institute’s Visual Arts Center] (see documents 743800, 744085, and 761879). It depicts a Christ mounted on a US Air Force bomber that is plunging Earthward. Ferrari was involved in the political conceptualism movement of the seventies (particularly Tucumán Arde, in 1968) [for Ferrari’s assessment of Tucumán, see (doc. no. 761415).]. In response to the most recent Argentine military dictatorship’s repressive regime (1975–83), he went into exile in Brazil, where he explored a variety of ideas, such as formalism and the reproducibility of a work, as well as the spatial relationship between sculpture and music (see documents 743960, 744392, and 743870, among others). In 1984 his work was once again exhibited in Buenos Aires, where he finally returned and settled until his death in 2013.

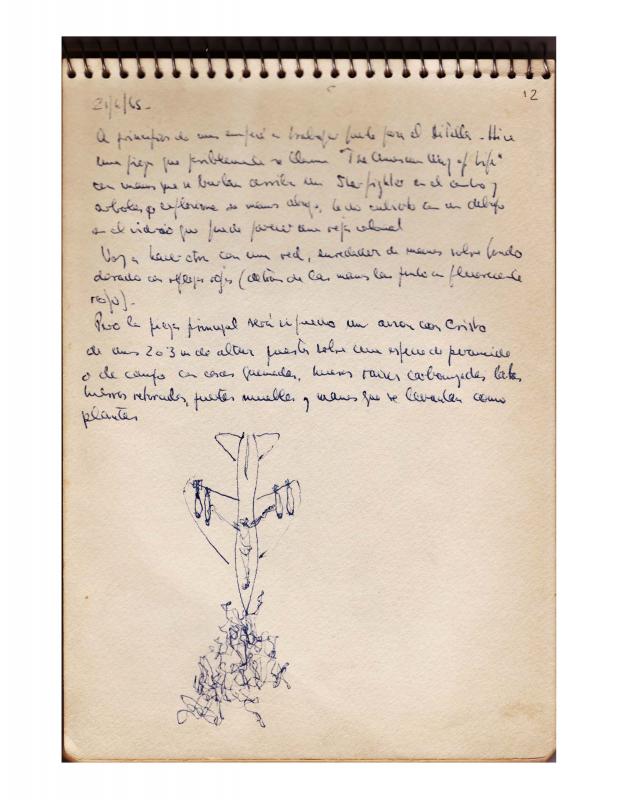

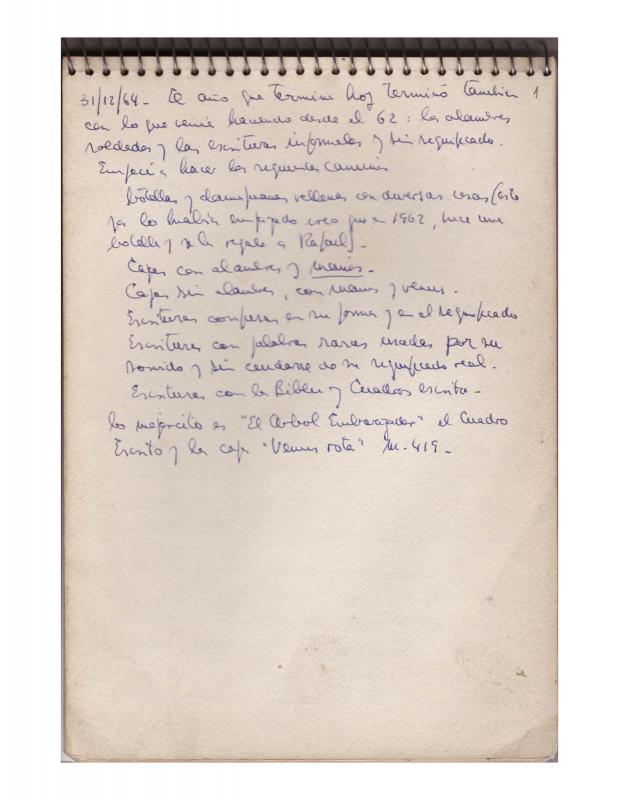

This written drawing dated December 1, 1964, comes from Ferrari’s series Manuscritos, realized between late 1964 and mid-1965. In parallel, on December 17, 1964, Ferrari created his celebrated El Cuadro escrito [Written painting], an ink-on-paper text-based composition, executed in an ornate, highly stylized cursive (doc. no. 743797). In contrast to his earlier, abstract calligraphic drawings from the period from 1962 to 1964, both El cuadro escrito and Manuscritos can be deciphered and read. Even though their texts are mostly humorous and grotesque in tone, they contain programmatic statements and parables, many of which aim at the U. S. imperialism and Catholic Church. Ferrari would continue these critiques throughout his career.

This text was published in English as “Art, my son…” in Mari Carmen Ramírez and Héctor Olea, eds., Inverted Utopias: Avant-Garde Art in Latin America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 483.