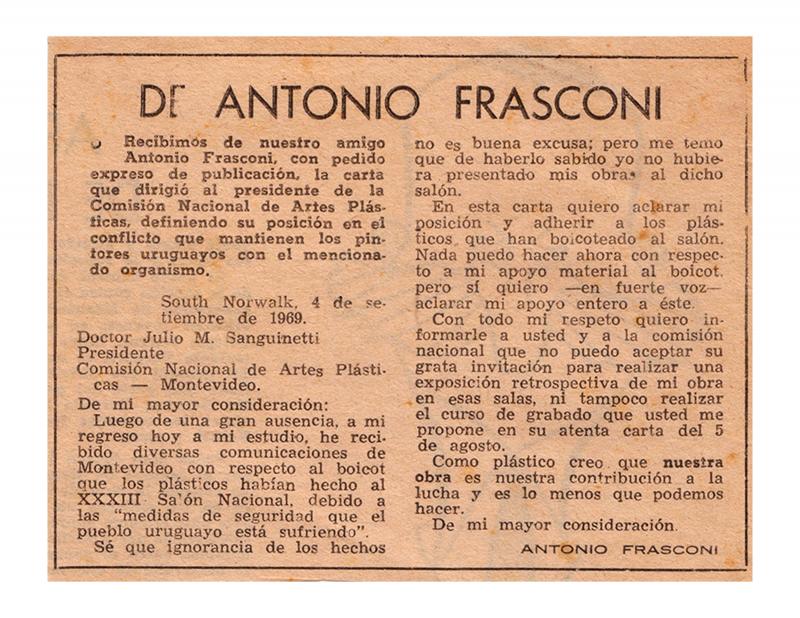

This interview with Antonio Frasconi (1919–2013) by art historian and essayist Gabriel Peluffo (b. 1946) was controversial. It is not surprising that the apparent contradictions in the Argentinean-Uruguayan artist’s statements would cause a stir at a delicate political juncture ripe for misinterpretation due to prejudices and ideological suspicions. Frasconi calls himself an “art worker with things to say”—and he says them through figurative art that looks to both old and new means of expression. A celebrated printmaker who worked in woodblock, silkscreen, and lithography, Frasconi was not hesitant to incorporate into his work photography and other materials (string and cardboard, for instance). In the abstract-figurative debate, he maintained that the first partook of a contemporary decorativeness that he deemed lacking in content. Upon moving to the United States, he began pursuing a humanist tendency in art concerned with world conflicts (significantly, the Vietnam War was underway). A teacher as well as an artist, Frasconi led “a modest […] life, making more personal work.” Nonetheless, he was engaged in the social and political debates taking place in the United States, and in Uruguay and Latin America. Frasconi appreciates the middle class power of sales and consumption in the United States, owing to that which an artist’s work can be “absorbed” and can find a place “among people, not in a museum.” In Uruguay, on the other hand, creators can rarely make a living from their work. His reflections sum up the various perspectives of diaspora artists who coordinate, with different degrees of commitment, engagement with the places in which they live and engagement with their countries of origin. Frasconi states that he consciously attempts to join art and politics with a focus on contemporary artistic practices. Notwithstanding, one of his statements was particularly polemic: “Here [in Uruguay] an artist that wants to make a living from his work has to leave [...] It might be individualistic or selfish, but everyone must seek satisfaction.” In the context of a Uruguay riddled with sociopolitical conflict, those words did not sit well with radicals (focused on the local context and social solidarity), let alone with the student body at the university where Frasconi was showing his work. [For further reading, see the following texts in the ICAA digital archive: by Mario Benedetti “El grabado uruguayo en la Exposición de La Habana” (doc. no. 1241970); and by Antonio Frasconi “Carta abierta de Antonio Frasconi” (doc. no. 1246348)].