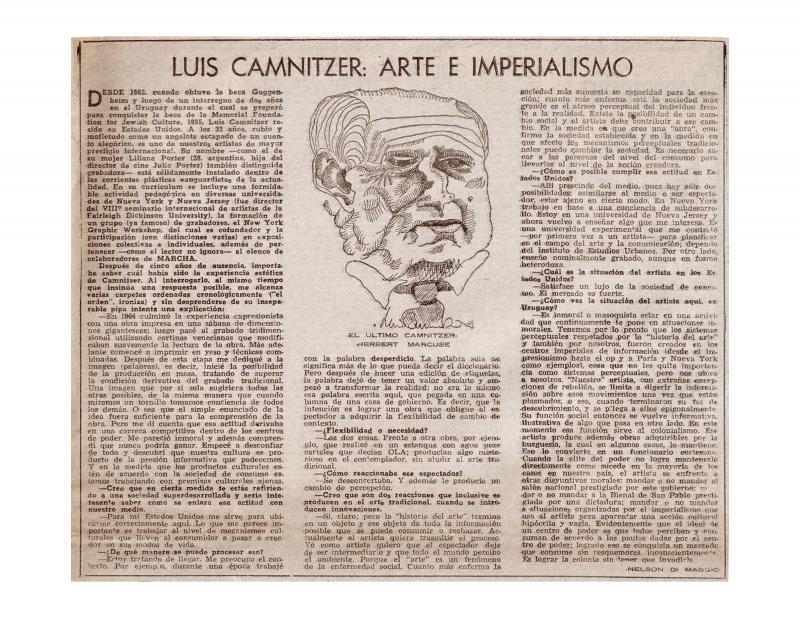

Under the title of “Las bienales también mueren,” the Uruguayan art critic Nelson DiMaggio, born in 1928, reflected and would warn about various local topics regarding international events and international artistic agents, such as biennials, exhibition halls, and art dealers, which began to get blurry, consequently complicating their primary and original significance. [Please refer to the ICAA digital archive for the following text: “IX Bienal de Sao Paulo. Demasiadas antítesis” (doc. no. 1233548)]. Di Maggio explored the tenth São Paulo Biennial, which was, in his opinion, the “only center for artistic information on the continent, a guide for visual artistic creation in those countries that are far away from the large artistic production centers.” The art critic ironically warned that the principal denouncement and boycott of the biennial came from the artistic centers of power. As an example, the Non à la Biennale that was articulated from Paris where these events were considered “spectacles that were instituted by the capitalist bourgeois monopolies.” [Please refer to the ICAA digital archive for the following text: “Entrevista a Pierre Restany,” by Nelson DiMaggio (doc. no. 1241306)] The terminology of the article appeals to a political, cultural, regional, and international environment that displayed several connections. On the one hand, the global bipolarity that was generated by the Cold War, and from a regional point of view, was the undisguised supervision by the United States of the Latin American cultural emergence under international codes of dependence. Add to this, the increasingly antiestablishment and tense attitude of the art critics and artists toward the various agents and cultural networks of power after the mid sixties. [Please refer to the ICAA digital archive for the following texts: [“Luis Camnitzer: arte e imperialism,” by Nelson DiMaggio (doc. no. 1244924) and “El artista como payaso,” by Angel Rama (doc. no. 1244987)]. Amid this complex, radical climate, Di Maggio describes the official position of Uruguay, which, despite being a border country of Brazil, acted as an indifferent participant to the conflicts unleashed at that time, without hesitating a bit in presenting art work at the tenth Bienal Internacional de São Paulo in 1969, and his artistic critique, designating as its representative, Ángel Kalenberg.