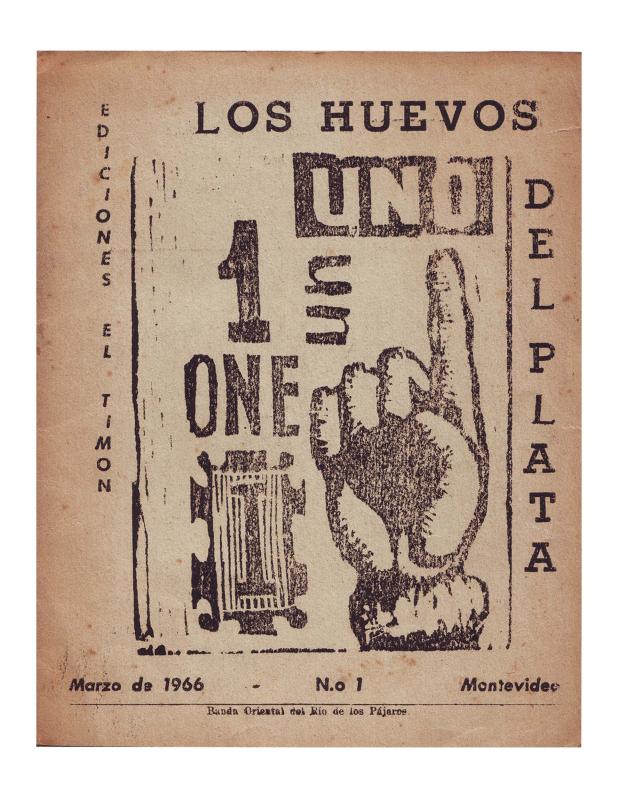

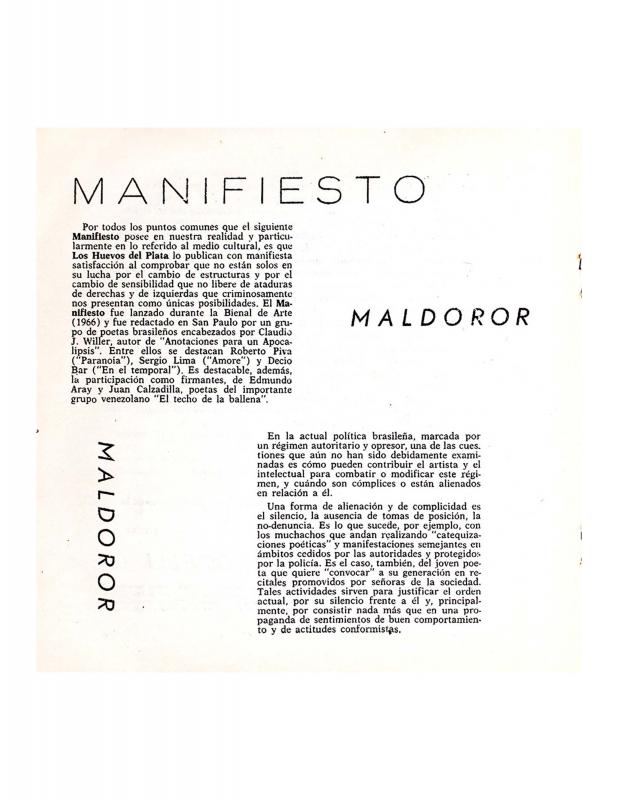

The Cuban Revolution strongly influenced Latin American thinking. It demonstrated that not only did it make sense to develop challenging strategies against institutions, but that there were also possibilities for the existence of “utopia.” At end of the sixties, there was a surge in ideological clashes and social movements in Latin America that resisted the oppressive and authoritarian military regimes in most of the countries of the continent. In the particular case of Argentina, a collective group of intellectuals and artists of different disciplines promoted the insertion of avant-garde art into the social fabric. And in the case of Rosario, the movement that had developed at the time was headed by several groups, was named Ciclo de Arte Experimental, and was composed of Eduardo Favaro, Graciela Nevadoe, and others. However, the main writers and theorists who wrote the basic texts were Juan Pablo Renzi, María Teresa Gramuglio, and Nicolás Rosa. The visual artist León Ferrari, who wrote other texts at that time, summarized the generalized approach in a sentence: “We must change the audience.” Toward the end of 1968, an event named Tucumán Arde was organized first in the city of Rosario, and then in Buenos Aires, initiating a series of discussions focused on the possibilities of creating a cultural phenomenon that would play a completely confrontational role with respect to artistic policies imposed by the dictatorship of General Juan Carlos Onganía (1966−70), especially in relation to the crisis of the sugar mills in Tucumán, an impoverished northern state in Argentina, ironically called “El Jardín de la República [The Garden of the Republic],” which was also, incidentally, one of the titles of the multiple events. This artistic project was taken to the limit of political conformity as the activities of resistance by the revolutionary political groups reflected the artistic practices like a mirror. The Uruguayan artist Clemente Padín (b. 1939) in his magazine OVUM 10, published a reflection on activities of the avant-garde collective group Tucumán Arde and its promotion of avant-garde artistic projects, similar in way, to “alternative cultural strategies,” rejecting works created as enduring and “unique objects.” It is interesting to note that artistic events recorded at that time in Uruguay were far from what was being proposed in Tucumán Arde. And, the polemics on artistic propositions or politics not been recorded as the Argentinean artists were doing in 1968. [Please refer to the ICAA digital archive for the following texts: “Arte en las calles,” by Clemente Padín (doc. no. 1243093), [Manifiesto Los Huevos del Plata] (doc. no. 1243157), and [Manifiesto Grupo Brasileño Maldoror] (doc. no. 1243177)].