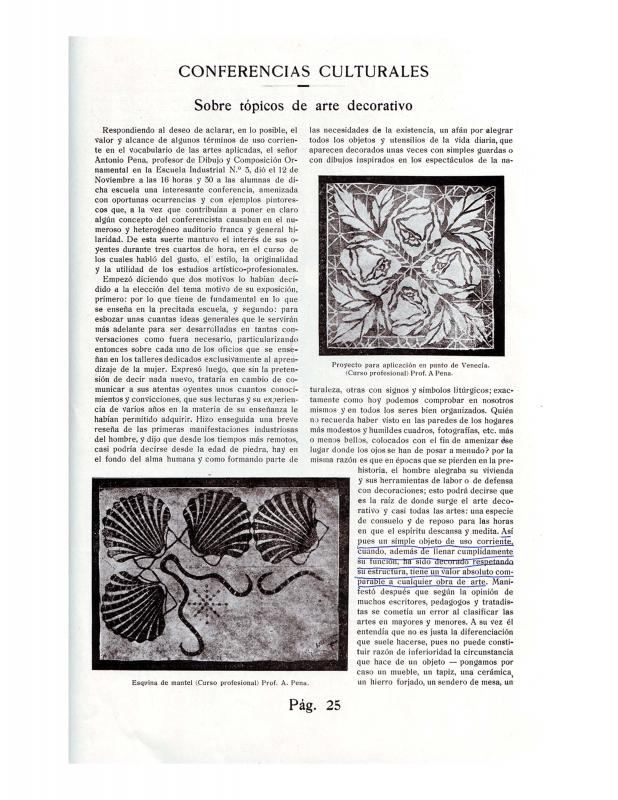

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, a number of Uruguayan painters—among them Carlos Federico Sáez (1878–1901), Milo Beretta (1875–1935), Pedro Blanes Viale (1879–1926), and Carlos María Herrera (1875–1914)—traveled to Europe. They brought back with them the spirit of artistic renovation they had encountered in France, Spain, and Italy. In 1905, a group of individuals associated with the university in a number of fields tied to the industrial and commercial sector founded the Círculo Fomento de Bellas Artes (CFBA) to promote a new artistic culture rooted in modernism. Carlos María Herrera was made director of that institution’s school. As both an artist and an educator, Herrera strove to strike a balance between an interest in renovation and the muddled artistic curiosity of the educated bourgeoisie surrounding the CFBA. He was able to reconcile the romantic essence of the moment and the aristocratic apprehension and unease with the reigning prosaic bourgeois taste. From 1905 until 1943—the year when the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes was created—the CFBA was the breeding ground of the most representative figures in Uruguayan art, many of whom later taught at its school. The members of the CFBA included painter Carlos Alberto Castellanos (1881–1945), cofounder of the Sociedad Amigos del Arte; critic and historian José María Fernández Saldaña (1879–1961); Catalan painter Vicente Puig (1882–1965), who, along with Herrera, established the two primary strains of the CFBA school; sculptor Luis Falcini (1889–1973); architect Eugenio Baroffio (1877–1956); and architect Alfredo Jones Brown (1876–1950). This document attests to Herrera’s decision to eliminate the use of plaster models, an academic technique, and replace it with “open air” techniques that involved observation of the flora and fauna found in nature. He wanted to do away with aesthetic parameters that had been established in the nineteenth century to instead incorporate instruction based on positivist and idealist principles. He was also concerned with training craftsmen in the design of styles and in the application of artistic principles to the decorative arts—an approach he thought would win support from the local industrial sector—in line with the ideas upheld by Pedro Figari (1861–1938) at the time. Just as the Pre-Raphaelites rejected the academic art dominant in England in the nineteenth century, Herrera repudiated academicism in instruction at the CFBA School, instead advocating meticulous drawing and “luminous painting.” [For further reading, see the following texts in the ICAA digital archive: “Consideraciones sobre aspectos de la enseñanza del dibujo” by Guillermo Rodríguez (doc. no. 1230412); “Conferencias Culturales. Sobre tópicos de arte decorativo” by Sebastián Viviani (doc. no. 1230583); and “El Círculo de Bellas Artes y su acción docente 1905–1938” (doc. no. 1231073)].