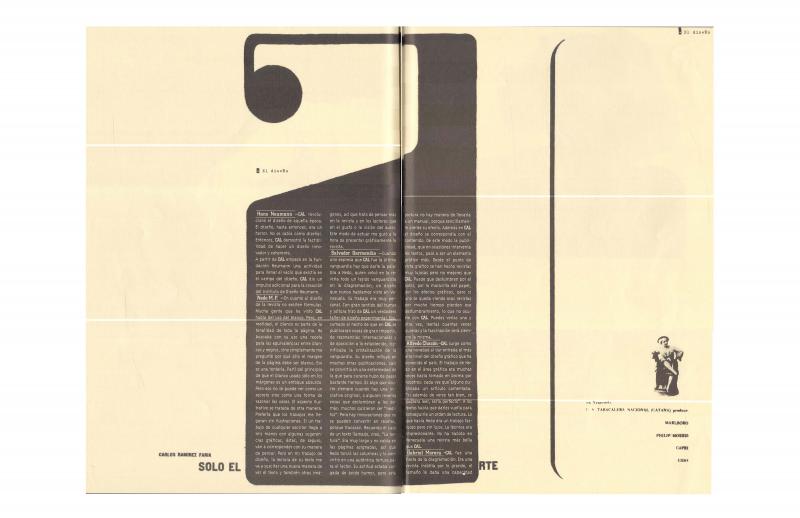

The catalogue to the exhibition CAL: la última vanguardia held at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Caracas Sofía Imber in Caracas in 1996 not only provides a historical revision of that important publication, but also includes valuable testimony from those who participated in it. Dedicated to criticism, art, and literature, the magazine CAL—which was published from 1962 to 1967—is an example of the integration of the arts; those who make statements in this text explain that, in keeping with the thinking of the sixties that placed value on plurality and difference, CAL was able to bring together different tendencies in an avant-garde initiative that did not belong to any of them. Rather than reflect an “official” aesthetic or discourse, CAL managed to bring together a common and diverse opposition to the system, providing it with a voice while conveying a visual code. Both its distance from the status quo and the catalyst effect of its plural approach transformed the experience of an incipient democratic process that facilitated expression and creative freedom regardless of harsh criticism. The magazine’s artistic director, Nedo [Mion Ferrario] (1926–2001), did striking work in graphic design in relation to the publication’s process—which he confesses was a bit improvised—and to the freedom of association that helped make CAL a milestone in the history of design in Venezuela. The idea of structuring a text on the basis of images is in keeping with the exploration of new fields of artistic expression. Taking on new problems meant developing new graphic solutions. CAL’s commitment to integration indicated a new concern with a broader notion of “culture” linked to the literary and journalistic background of the magazine’s founders.

The cover of the fifth issue of the magazine evidences a support of novelty that did not eschew tradition. The illustration combines a representation of Edme Moreau’s 17th-century The Triumphal Arch of Death with a second image, probably by Jacobo Borges, the author of the article “El canto de la muerte” which opens this issue. Borges devises an idea-script for a work that brings together theater, painting, poetry, and music—an exercise of artistic integration that makes use of tools used by avant-garde groups in Venezuela, such as El Techo de la Ballena, insofar as it makes reference to the literary tradition (see the altarpiece or memento mori genre). That same approach is at play in Nedo’s design; for him, the fact that the magazine was avant-garde did not mean that it rejected the imaginary of the European tradition. This coming together of visual codes is what made CAL a unique and pioneering experiment.

[For other texts and statements by various authors published in CAL, see in the ICAA digital archive “El surgimiento de CAL” (doc. no. 1169178); “Arte, vanguardia y nuevas figuras” (doc. no. 1169254); and “El diseño” (doc. no. 1169217)].