The assessment of the neo-academic painting created by the Venezuelan painter Pedro Centeno Vallenilla (1904–1988) has led to profound disagreements in Venezuela. In spite of early support from a writer as well known as Arturo Uslar Pietri, the avant-gardes that appeared in the 1950s and 1960s made it clear just how ordinary and anachronistic this showy painting was. They focused on its idealistic exaltation of native heroes, its folkloric elements, and especially, the artist’s series on the caciques. In his heyday, which coincided with the last dictatorship of General Marcos Pérez Jiménez (1952–58), the artist did have impact. Some years later, in the early 1970s, the inclusion of his work in the historian Rafael Delgado’s Colección Pintores Venezolanos marked the appearance of more tolerant and accepting opinions. This volume included significant data and previously unknown references to articles about the artist in periodicals. (One example was an article by the Italian Latin-Americanist G. V. Gallegari, who had published an early study on the work of Centeno Vallenilla in the journal La Razza in 1940.) For its part, Delgado’s text has the merit of being the first notable monograph on the questionable painter who portrayed heroes and caciques. In this regard, the article concentrates on pointing out the artist’s questioning of twentieth-century avant-gardes as well as his ties to Latin American painting. The writer also notes the artist’s handling of sensuality in his figures.

The unique qualities of Centeno Vallenilla’s art in Venezuela are more relative in the broader context of Latin American art. Other contemporary artists included Francisco González Gamarra (Peru) and Jesús Helguera (Mexico), though the work of both these artists is more baroque than classical. Only for a posthumous exhibition of Centeno Vallenilla’s work at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Sofía Imber (Caracas, 1993) would the artist be given a less passionate assessment, less bound to a given time period. The critics who wrote the new assessment were Francisco Da Antonio and María Luz Cárdenas.

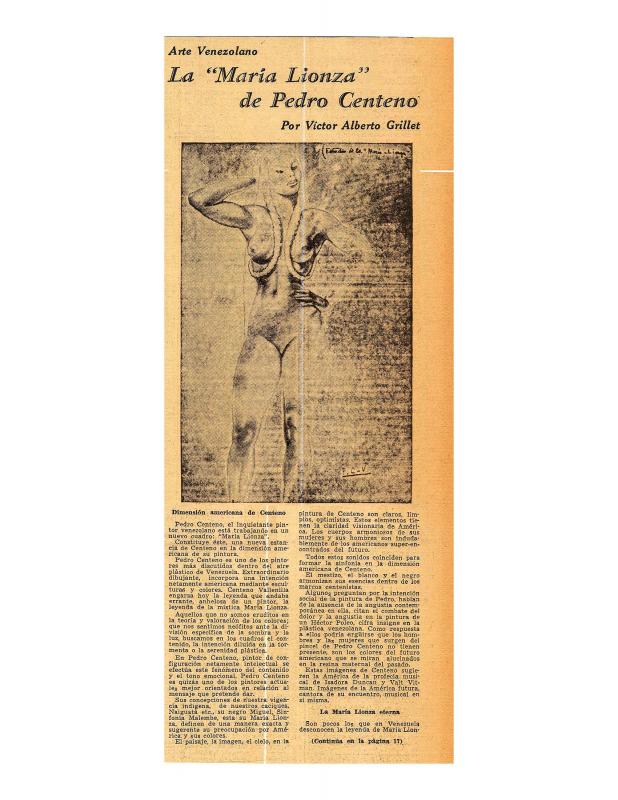

[For another text on the work of Centeno Vallenilla, see “La ‘María Lionza’ de Pedro Centeno” by Victor Alberto Grillet (doc. no. 1172037)].