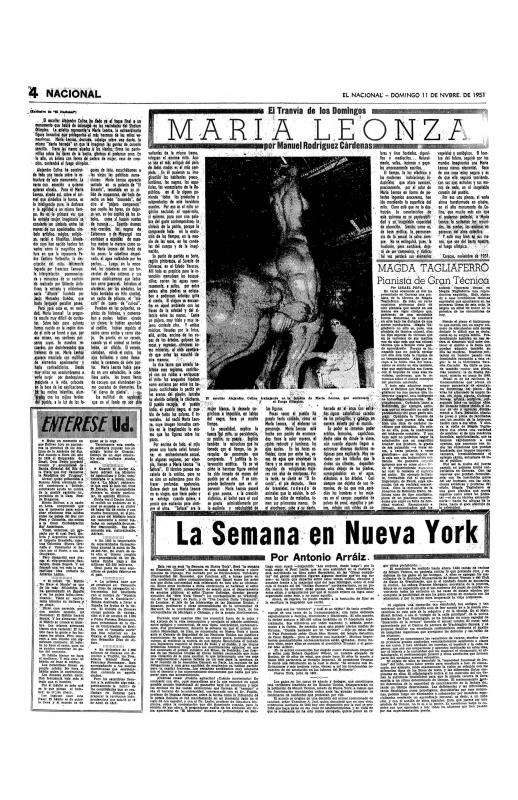

The importance of this article by Venezuelan cultural activist Manuel Rodríguez Cárdenas (1912–1991) stems from it being the first to raise the alarm about the deterioration of the monument to María Lionza (1951), created by the Venezuelan sculptor Alejandro Colina (1906–1973). The author’s concern derives from his having served as a consultant to the artist (as well as publicist), both with regard to this statue—which was chosen by the Ministerio del Trabajo [Ministry of Labor] to act as an Olympic torch during the III Juegos Deportivos Bolivarianos [Third Bolivarian Games]—as well as other [statutes] connected to the indigenous history [of Venezuela] (the native Yaracuy, in San Felipe; Chief Manaure in Coro City). Initially intended to be placed in front of the stadium at the Ciudad Universitaria in Caracas, during the mid-1960s it was transported by the Ministerio de Obras Publicas [Ministry of Public Works] to the center of the Autopista del Este [Eastern Highway]. This led to a slow deterioration caused by the vibrations of automotive transit; in addition to this, an urban cult grew up [around the statue] (therefore the floral offerings) that included climbing the monument. The author therefore pleads for another transfer; this time to a wooded zone, more in accord with the symbolism of the indigenous, African, and criollo myths, in Los Caobos park.

Since the transfer never occurred, the proposal is now seen as the precursor of a concern that would resurface in the 1980s (and more recently in 2004) given the grave deterioration of the monument, and the uncertainty regarding which institution is responsible for its restoration (Municipalidad de Caracas, Galería de Arte Nacional, or Universidad Central de Venezuela). After one year of harsh debate (strongly charged politically due to the definitive fracture of the monument), the Tribunal Supremo de Justicia [Supreme Court of Justice] ruled that the Universidad Central of Venezuela should undertake its restoration. The municipal government replaced the monument with a copy made with modern materials (polymers), although the eventual location of the original work was still undecided.

The myth and cult of María Lionza has transcended Venezuelan boundaries, and has deep folk roots within marginal zones; this statue began to be reproduced in different sizes and materials beginning in 1973 (date of the artist’s death) for the altars of devotees of “la reina” [the queen] María Lionza. Today both the image and myth of María Lionza are recognized by anthropologists, critics, and urban studies professionals as belonging to the collective Venezuelan imaginary and also as an urban landmark of Caracas.

For more on this topic, see the other text by this author in the ICAA digital archive, “El tranvía de los Domingos: María Leonza” [The Sunday Tram: María Leonza” (doc. no. 1102427)].