This essay—in which the curator and critic Katherine Chacón writes about Javier Téllez—was published in the catalogue for the exhibition La extracción de la piedra de la locura (Caracas: Museo de Belllas Artes, 1996). Chacón’s piece about Téllez’s installation appeared before the lengthy preface by Carmen Hernández, who curated the show. This essay provides vital biographical information that helps to understand this Venezuelan artist’s work. For example, Chacón mentions factors that contributed to the emergence of “the phenomenon” created by Téllez who, in addition to his precocious talent and his passion for reading, has had a lifelong interest in the world of psychopathology (his father is a psychiatrist).

Chacón has no hesitation in placing the work that Téllez has produced ever since his early painting period among the most “innovative—and fresh—contributions in contemporary Venezuelan painting.” One of the useful features of this essay is Chacón’s review of the various periods in Téllez’s career, which she explores as she documents his steady development toward objectual art. She notes that his early work was influenced by Mario Abreu’s “magical objects,” but that from that point on it was distinguished by its formal simplicity and moderation.

The periods that Chacón suggests in her essay are as follows: the early paintings, executed with formal boldness and an expressionist technique involving rapid brush strokes, featuring “tormented portraits” of distorted faces expressing pain. His second period consists of works that already show his use of his own pictorial language, with no acknowledgement of styles in vogue or current trends. He then moves away from painting to explore the expressive potential of objects. Here, Chacón mentions his painted objects and his later objets-trouvés [found objects], which are defined by a certain archaism that suggests a kind of daily activity that has almost fallen into disuse.

The installation La extracción de la piedra de la locura was one of the most thought-provoking exhibitions in Venezuela at that time; it prompted a somewhat unusual reflection on madness, which was a difficult subject to address, and one that Téllez would continue to explore in ever greater depth. It is interesting to note what Chacón has to say about the installation’s conceptual platform: “perhaps” the ideas that support his artistic work have some connection to anti-psychiatric arguments, which claim that there is no such thing as madness.

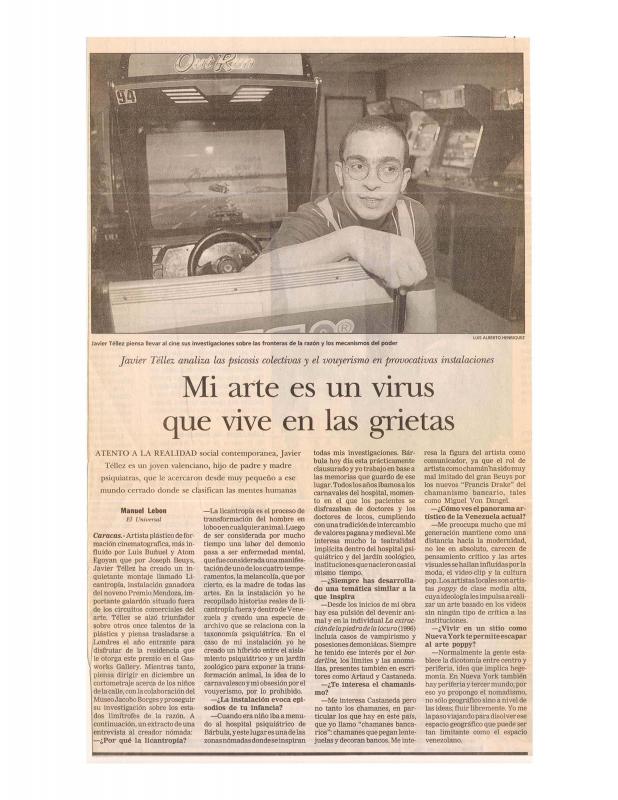

To read other articles about Téllez and his work, see by Rubén Gallo “Del mausoleo al juego en cuatro imágenes / From the mausoleum to the playroom, in four images” [doc. no. 1155086]; by Carmen Hernández “La extracción de la piedra de la locura: una instalación de Javier Téllez” [doc. no. 1154986]; Ruth Auerbach’s interview “Trobar clus: de cómo despistar al expectador” [doc. no. 1154795]; Manuel Lebon’s interview “Mi arte es un virus que vive en las grietas” [doc. no. 1154938]; and the review by Ana María Mendoza “La pieza ‘Licantropía’ obtuvo el premio Eugenio Mendoza” [doc. no. 1154954].