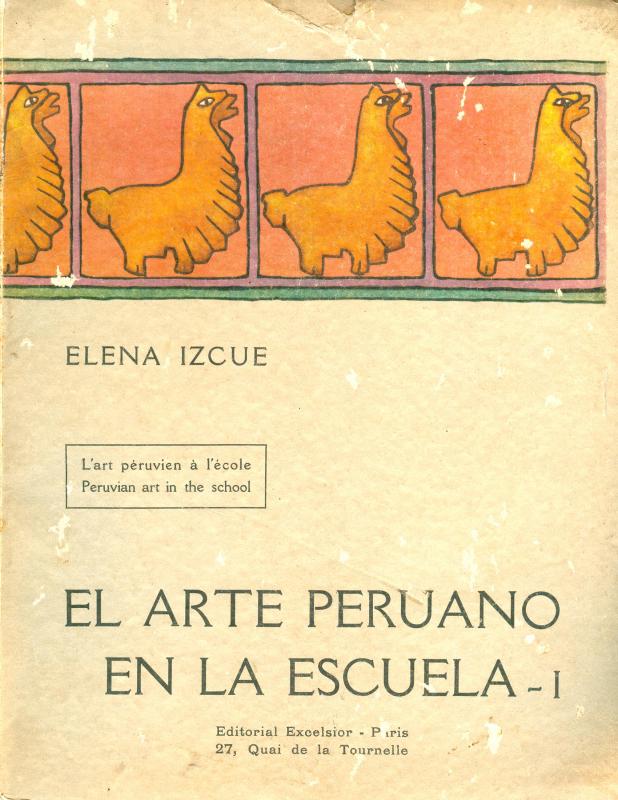

The 1920s witnessed the birth of a modern movement in Peru that looked to pre-Columbian art and influenced the development of archeology as well as the search for sources of national identity advocated, during the period, by Indianism. Artists, researchers, and intellectuals investigated pre-Columbian motifs which, in the realms of the decorative and functional arts, they adapted to contemporary life. Artist Elena Izcue was crucial to this movement. At the margins of the Indianist group led by José Sabogal (1888–1956), she produced outstanding textile designs and works of applied art that brought her into contact with the fashion industries of Paris and New York. In 1927, thanks to a two-year fellowship from the Peruvian government, Elena and her sister Victoria went to Paris to further their studies in art. Pursuant to work in a number of different studios and workshops, their career in the decorative arts flourished. Known for fabrics printed with patterns inspired by pre-Hispanic art, their works were purchased by the House of Worth and other prestigious fashions houses, as well as private clients. In 1935, the Izcue sisters traveled to New York where, thanks to the efforts of philanthropist Anne Morgan (1873–1952), an exhibition of their works of modern art, along with pre-Incan textiles and ceramics, was held in the galleries of the Fuller Building. After the show closed, the sisters stayed on in New York for a few months to make works commissioned by different firms. In mid-1936, they returned to Paris where they resumed work in textile design. They were commissioned to decorate the Peruvian pavilion at the International Exposition of Art and Technology in Modern Life in 1937. For that project, they selected models, photographs, and samples of industrial products that provided a modern image of Peru, as well as works by contemporary artists. In the gallery of honor, works by the Izcues were on display alongside pre-Hispanic pieces. El arte peruano en la escuela, which was published in Paris, earned Izcue recognition both locally and internationally. The book included versions of the texts in English and in French, which meant that it reached Americanists throughout Europe and, thanks to Ventura García Calderón and Rafael Larco Herrera, schools and artistic circles in North America. The press covered the arrival of the first copies in Lima in early 1927 extensively; reviews by Elvira García y García, Magda Portal, and Dora Mayer de Zulen placed emphasis on the fact that, if given to children, the workbook would provide local models capable of generating nationalist identification. Indeed, the workbooks were used to teach art in a number of schools in Peru. Judging from the simplicity of the motifs and their organization, the first workbook appears to have been primarily geared to small children, whereas the second—which contained a section on applications in the decorative arts—appears to have been aimed at artisans and more advanced students. Though based on pre-Columbian works, the figures, in both cases, are envisioned as autonomous, and design is privileged for its own sake. The prologue was written by Peruvian writer, diplomat, and literary critic Ventura García Calderón. He lived in Paris most of his life, and much of his production—which includes stories with modernist tone set in the Andes—was written in French. García Calderón has been criticized for his ignorance of life in the Peruvian countryside and for his biased vision of indigenous peoples. His vision partook of early positivist Indianism, which emerged at the beginning of the twentieth century, according to which the debased and inferior condition of indigenous peoples was not natural, but rather the result of Spanish domination that kept them at the margins of European civilization. According to that view, the Indian, if educated, could be transformed entirely. The author of the second text, Elvira García y García, was a pioneer in women’s education; she founded, directed, and taught at a number of schools in Lima. In 1883, for instance, she founded the Liceo Peruano for the education of young women; from 1894 to 1914, she was the principal of the Liceo Fanning, which—along with the Colegio Nacional de Mujeres, which she directed from 1931 to 1941—was a breeding ground of Peruvian women intellectuals. García y García contributed to a number of publications and wrote several books, among them Educación femenina (1908) on the social mission of women in the Americas and La mujer peruana a través de los siglos (1924–35). [For further reading, see in the ICAA digital archive the following articles: Elena Izcue’s “El arte peruano en la escuela” (doc. no. 1146099); by “Racso,” pseudonym of Óscar Miró Quesada de la Guerra, “Un noble ideal artístico: las hermanas Izcue en París” (doc. no. 1144316); Elvira García y García’s “Una artista peruana en París” (doc. no. 1144288); Alberto J. Martínez’s “En el Museo Nacional: un ensayo de decoración estilo incaico” (doc. no. 1144009); Rafael Larco Herrera’s “Las señoritas Izcue y el arte del antiguo Perú” (doc. no. 1143993); and Manuel Solari Swayne’s “Manuel Piqueras Cotolí” (doc. no. 1141324)].