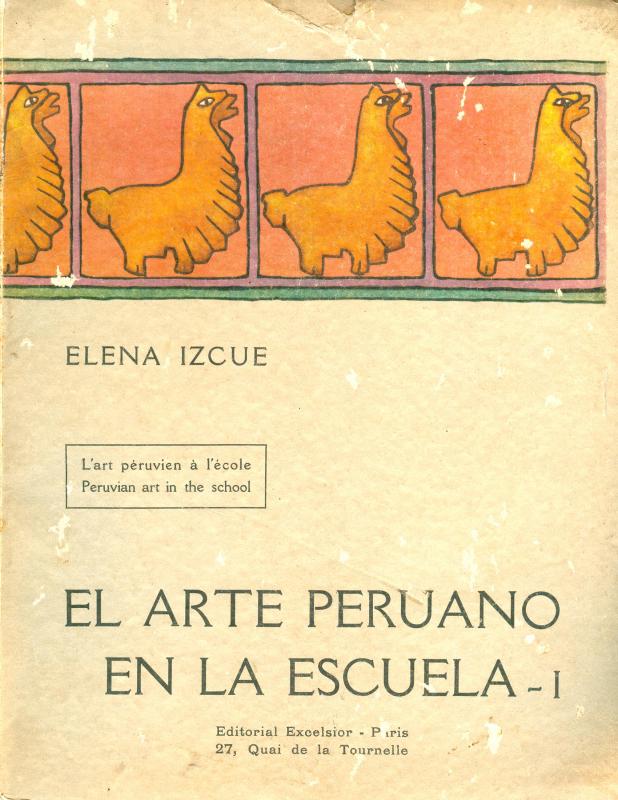

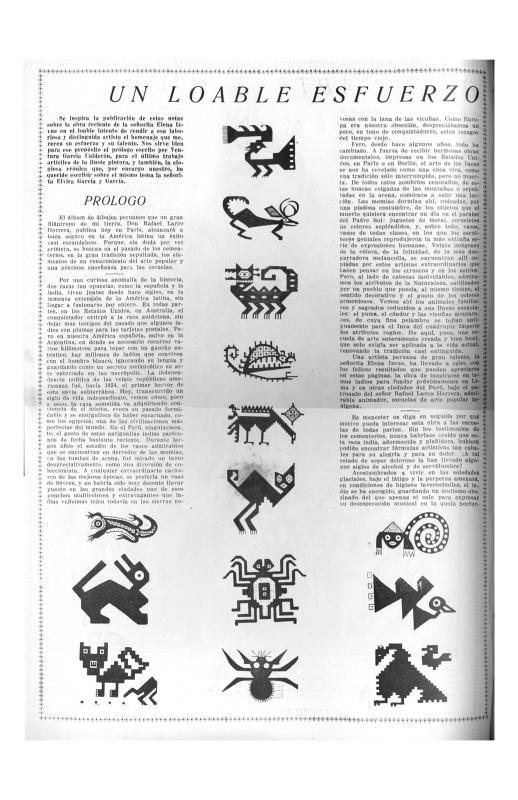

The 1920s witnessed the birth of a modern movement in Peru that looked to pre-Columbian art and influenced the development of archeology as well as the search for sources of national identity advocated, during the period, by Indianism. Artists, researchers, and intellectuals investigated pre-Columbian motifs which, in the realms of the decorative and functional arts, they adapted to contemporary life. Artist Elena Izcue was crucial to this movement. At the margins of the Indianist group led by José Sabogal (1888–1956), she produced outstanding textile designs and works of applied art that brought her into contact with the fashion industries of Paris and New York. In 1927, thanks to a two-year fellowship from the Peruvian government, Elena and her sister Victoria went to Paris to further their studies in art. Pursuant to work in a number of different studios and workshops, their career in the decorative arts flourished. Known for fabrics printed with patterns inspired by pre-Hispanic art, their works were purchased by the House of Worth and other prestigious fashions houses, as well as private clients. In 1935, the Izcue sisters traveled to New York where, thanks to the efforts of philanthropist Anne Morgan (1873–1952), an exhibition of their works of modern art, along with pre-Incan textiles and ceramics, was held in the galleries of the Fuller Building. After the show closed, the sisters stayed on in New York for a few months to make works commissioned by different firms. In mid-1936, they returned to Paris where they resumed work in textile design. They were commissioned to decorate the Peruvian pavilion at the International Exposition of Art and Technology in Modern Life in 1937. For that project, they selected models, photographs, and samples of industrial products that provided a modern image of Peru, as well as works by contemporary artists. In the gallery of honor, works by the Izcues were on display alongside pre-Hispanic pieces. In 1938, with the outbreak of World War II close at hand, the Izcue sisters decided to return to Peru, though they stopped in New York on the way. It was there that they were commissioned to work on the decoration of the Peruvian pavilion at the New York World’s Fair; the aim of the pavilion was to communicate the public works and social projects undertaken by the administration of President Benavides (in office from 1933 to 1939). In this case, the Izcues’ role was limited to laying out the pavilion’s galleries and the objects in them. They reached Lima in mid-1939 and, in 1940, the Taller Nacional de Artes Gráficas Aplicadas, which Elena directed and Victoria managed, was created. Starting in 1941, they worked on a craftsmanship development project in northern Peru that focused on traditional straw and wicker weaves. Under the supervision of the Izcue sisters, a number of school-workshops were founded in different cities. In all of them, the Izcues attempted to raise the artistic level of the original works and to improve their production quality, while also proposing new designs and patterns. Surprisingly, motifs based on pre-Columbian art were lacking; the sisters were concerned with salvaging and perfecting traditional methods in order to apply them to contemporary design. In the early forties, the Izcue sisters retired from public service. For the last twenty years of her life, Elena focused on her own textile designs, as well as more personal and intimate drawings and paintings. In 1999, Natalia Majluf and Luis Eduardo Wuffarden published Elena Izcue. El arte precolombino en la vida moderna (Museo de Arte de Lima), the most thorough study of the artist’s life and work to date. The author of this text, landowner and philanthropist Rafael Larco Herrera, was a collector of pre-Hispanic Peruvian objects and a supporter of Elena Izcue from the beginning. In 1926, he financed the publication of El arte peruano en la escuela, educational volumes produced by the artist. Larco Herrera was the owner of Chiclín (La Libertad) estate, where he attempted to create an innovative educational, social, and business model. He was the force behind the founding of several schools that made use of new educational methods with a nationalist spirit. He was also the one who recommended that the Peruvian government grant Elena and Victoria Izcue the fellowship to travel to Paris. In 1931, he purchased La Crónica newspaper’s publishing company, and went on to preside over its board of directors for three decades. That newspaper frequently published articles on the Izcue sisters’ activities abroad. Larco Herrera also held a number of different public offices; from 1939 to 1945, he was vice-president of Peru under Manuel Prado. [For further reading, see in the ICAA digital archive the following articles: Elena Izcue’s “El arte peruano en la escuela” (doc. no. 1146099); by “Racso,” pseudonym of Óscar Miró Quesada de la Guerra, “Un noble ideal artístico: las hermanas Izcue en París” (doc. no. 1144316); Elvira García y García’s “Una artista peruana en París” (doc. no. 1144288); Ventura García Calderón’s “Un loable esfuerzo por el arte incaico: Prólogo” (doc. no. 1144261); Alberto J. Martínez’s “En el Museo Nacional: un ensayo de decoración estilo incaico” (doc. no. 1144009); and Manuel Solari Swayne’s “Manuel Piqueras Cotolí” (doc. no. 1141324)].