This report by Peruvian cartoonist and communication theorist Juan Acevedo (b. 1949)—the director of the Escuela Regional de Bellas Artes of Ayacucho in 1974 and 1975—enumerates the problems that his administration attempted to solve. In 1973, supervision of public art schools in Peru was handed over to the Instituto Nacional de Cultura, created in 1971 by the so-called Gobierno Revolucionario de las Fuerzas Armadas under General Juan Velasco Alvarado (1909–77). This document is one of the most articulate statements about the cultural ideology of a regime whose politics were known as Velasquismo. This text is part of a larger document by a number of authors entitled “Informe sobre la situación general de la formación artística en el país,” which encompasses areas such as music and dance as well.

As the director of the Escuela Regional de Bellas Artes of Ayacucho, Acevedo advocated reforms crucial to the new education policy. During his tenure, that school became the first institution to reformulate art education with relative success. The experiment, however, concluded once he left his post. Shortly thereafter, Ayacucho would become the cradle and primary stage for the Maoist Sendero Luminoso movement.

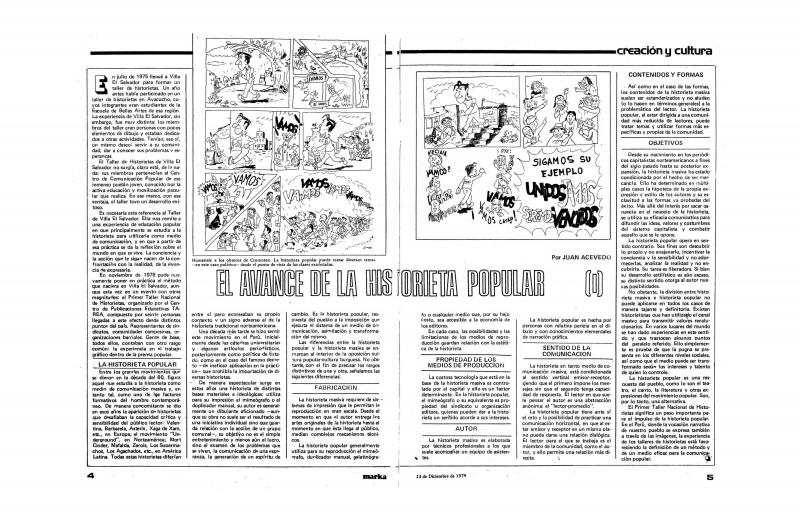

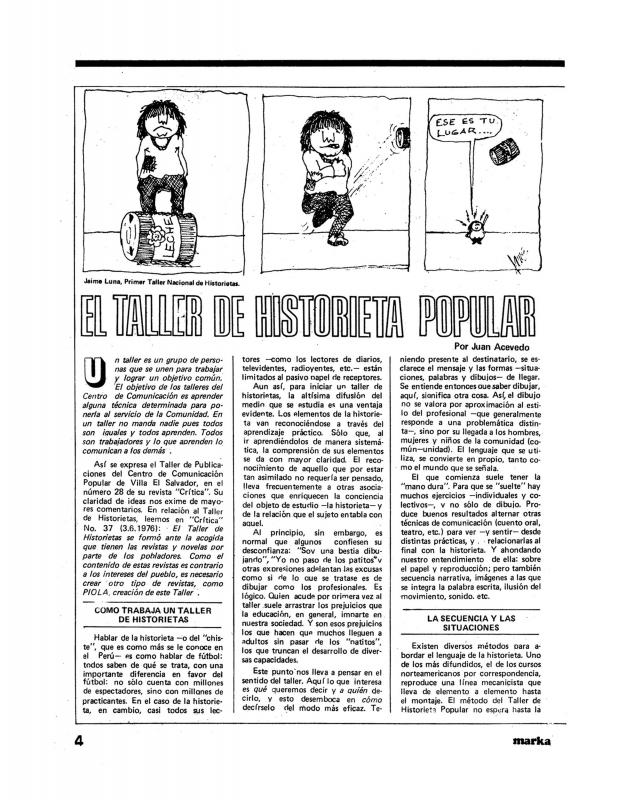

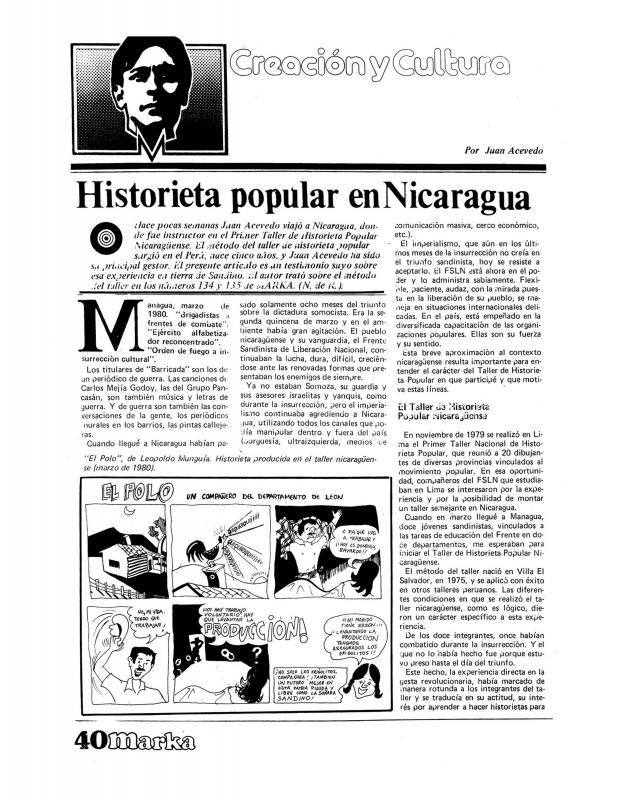

Acevedo is now recognized as one of the greatest Peruvian cartoonists; his most well-known creation is El Cuy, a guinea pig character closely associated with Peruvian leftist culture. Through his graphic work and workshops in popular communication, Acevedo supported Velasquismo, the economic, social, and cultural policies that were enacted during the first phase of the so-called Gobierno Revolucionario de las Fuerzas Armadas under General Juan Velasco Alvarado (1968–75). In 1978, Para hacer historietas was published. That celebrated book was based on the workshops he gave in the province of Ayacucho (1974) and in the Lima neighborhood of Villa El Salvador (1975), a section of the city that was representative of urban struggle. Para hacer historietas has been republished a number of times and translated into different languages. It upholds the idea that to make cartoons, it is not necessary to know how to draw; the systematized method has been applied to a number of different educational experiences in countries throughout Latin America.

[For further reading, see in the ICAA digital archive the following texts by Juan Acevedo: “El avance de historieta popular (I)” (doc. no. 1141902); “El taller de historieta popular” (doc. no. 1141933); and “Historieta popular en Nicaragua” (doc. no. 1139355)].