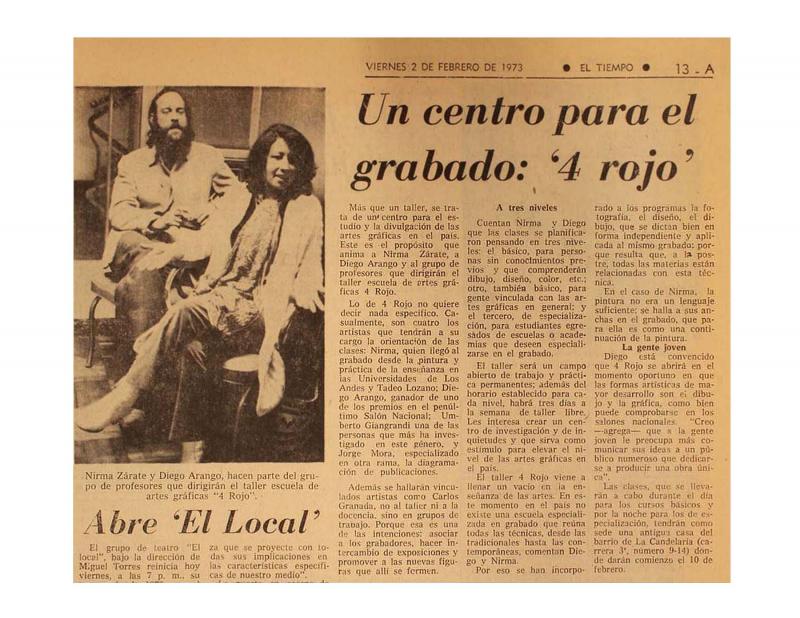

Regarding the date when the collective known as Taller 4 Rojo was founded, there is no agreement either by its members or by the art historians. Some historians, such as María Elvira Iriarte, date it back to 1970; others, such as Germán Rubiano Caballero, to 1972. The members have different versions of the founding as well; some say 1971, and others, 1972. Whenever it did get started, it is known that to begin with, the Taller operated in the La Candelaria neighborhood (in central Bogotá) and that it was a graphic arts workshop. The original directors were Diego Arango (b. 1942) and Nirma Zárate (1936–99), who had just returned from London, where they had studied graphic arts at the Royal Academy (between 1969 and 1970). Slowly other members joined the group, such as Jorge Mora, who was very knowledgeable about photographic techniques. Finally, it reached its full potential after it added the members Umberto Giangrandi (b. 1942) and Carlos Granada (b. 1933). The key to the group’s work was its interdisciplinary nature, involving its members not just as artists but also as members of social movements that began to take shape in the 1970s.

The Taller 4 Rojowas a meeting place for discussing the ways worker, student, peasant and Native movements must mobilize to claim their rights from the State. In this way, we can understand how useful it was to have access to the graphic arts along with their new production and printing techniques, which led the graphic arts away from traditional artistic purposes. Thus, the silk screen became a useful tool for making posters, placards, publications and pamphlets for social movements. That is why the founding of this Taller Escuela de Artes Gráficas 4 Rojo was so important: for training participants in the social struggles of the period. The emphasis placed by the leaders on studying the history and criticism of the graphic arts can clearly be seen in the classes offered and clarifications that appear in the document. Right from the start, Taller 4 Rojo understood the political potential of the graphic arts and the importance of training people to use them. It also supported a range of uses for these arts, beyond fine art, in one of the most intense political periods in Colombia’s history.

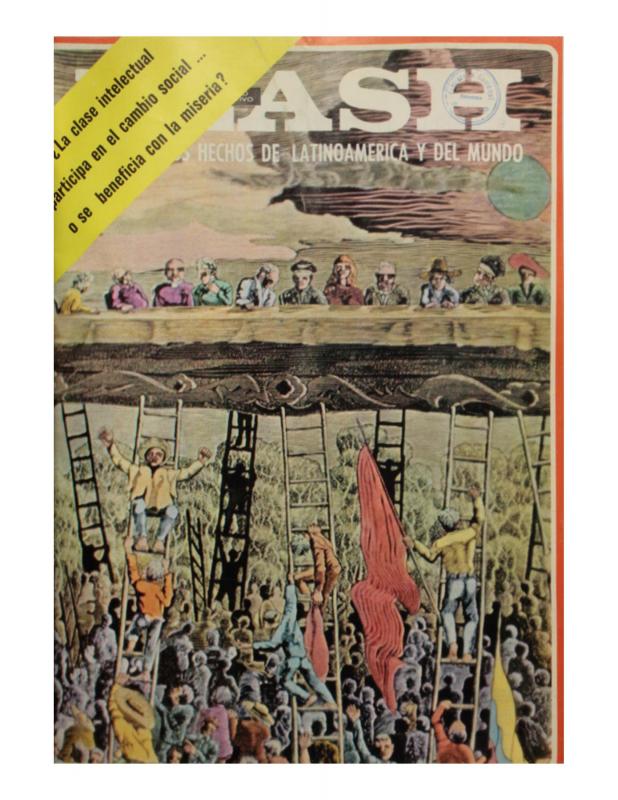

This text must be read in relation to two articles published in the press and in a journal [see “Un centro para el grabado: ‘4 Rojo’,” doc. no. 1133173; and “El debate queda abierto: ¿La clase intelectual participa en el cambio social o se beneficia con la miseria?,” doc. no. 1102659].