In this interview, the Colombian printmaker Luis Ángel Rengifo (1906−86) expresses his opinion on abstract painting. In those days he was interested in expressing “the vernacular” in his work, to the extent that he refers to his painting as “patriotic Colombian cultural works.” His words reveal his lack of interest in abstraction at a time when that style was gaining ground in Colombia, largely as a result of the sculptures produced by Eduardo Ramírez Villamizar (1923−2004) and Marco Ospina Restrepo (1912−83).

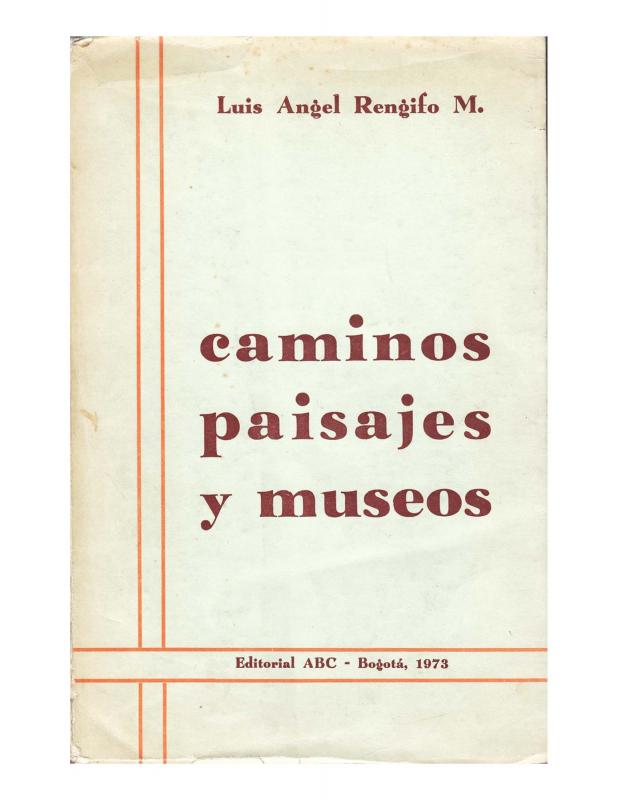

When asked about his plans for the future, Rengifo says he is anxious to go to Europe, visit the museums, and see the works of the great painters of the old continent. His dream came true in 1970, when he took a short trip and spent a few days touring Europe, which he recorded in his diary and published later, in 1973 [see “Bélgica: (Diario de viaje de 1970)”, doc. no. 1133788]. Rengifo spent a few years in Mexico City in the late 1940s, when printmaking was very popular there owing to the TGP (Taller de Gráfica Popular) that was founded in 1937 by a group of Mexican printmakers who were inspired by famous printmakers, such as José Guadalupe Posada (1852−1913). The educational nature of his prints showcases local iconic figures like Indians, rural peasants, and workers. It therefore comes as no surprise to hear that Rengifo was unimpressed by abstraction. He was far more interested in illustrative works with a social message, as in the case of his series of thirteen prints based on scenes of Colombian political violence.

Rengifo was appointed chancellor of the Colombian Consulate in Mexico in 1946 and was the Colombian vice-consul to Mexico from 1947 to 1950. He performed his diplomatic duties while studying printmaking at the Escuela de Grabado in Mexico City under the tutelage of draftsman and printmaker Francisco Díaz de León (1897–1975) and José Tullo. Rengifo is considered a pioneer of the printmaking boom in Colombia. Colombian art historians, such as Gabriel Giraldo Jaramillo and Álvaro Medina, and the Uruguayan Ivonne Pini all agree with this description, because on his return from Mexico, he reinstated the chair of printmaking and lithography of the arts faculty at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia (1951), where he was a drawing and printmaking professor. Furthermore, the prize he was awarded at the XI Salón Anual de Artistas Colombianos (1958) for his linocut Hambre (1958) confirmed the autonomy of this artistic language that for many years had been dismissed as a “minor art.”