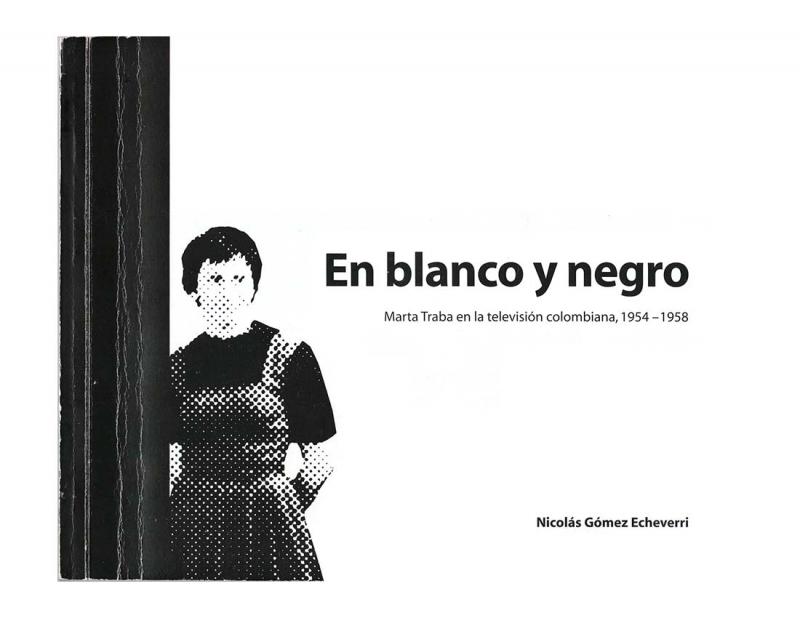

This interview with Gonzalo Ariza (1912–95) suggests a reading of art history opposed to that defended by the Colombia-based Argentine intellectual, Marta Traba (1923–83). Her criticism, in both written media and on television [see doc. no. 1131920] in defense of art avant-gardes made her one of the most respected and controversial critics during her long stay in Colombia. She carried on an intense dispute with Ariza about what the future of art should be in Latin America [doc. no. 1129558].

Traba’s philosophical stance informs an understanding of Ariza’s opinion on Colombian criticism, which he characterizes as “violent.” It is an indirect reference to Traba, stating that critics make great efforts to become “high priests, establishing an art trend or making it fashionable.” Ariza proceeds to classify criticism as “dictatorial” —as issued by television, art galleries, the Office of Cultural Programs, private businesses, and other Colombian cultural institutions, all of which favor abstract painting. The pro-abstract art list provided by Ariza gives us clues about the artistic preferences of the various cultural institutions, businesses, and art academies that supported the Colombian art community during the referenced period.

It is interesting to note the distinction suggested by Ariza between art created in the Pacific region—influenced by Eskimo, Mayan and Aztec cultures—and that created in the Atlantic region, in his opinion, dominated by European art. The reference he makes to European art is in the context of “the Colony,” under the influence of abstract art and Expressionism. He rejects these trends in the belief that the elements of the painting (line, colors, space) are rendered better in a figurative painting. However, Ariza’s theoretical beliefs did not prevent him from admiring the work of the Renaissance. His reading of art was influenced by his extremely personal point of view, which perceived a spiritual link between Latin America and Asia. Ariza believed that there was archeological evidence to support this perspective, based on the artist’s knowledge of Eastern painting and literature. After studying Japanese engraving in Tokyo between 1936 and 1938, Ariza returned to Colombia with a keen interest in investigating the characteristics of the Colombian landscape in the specific light of Japanese art.