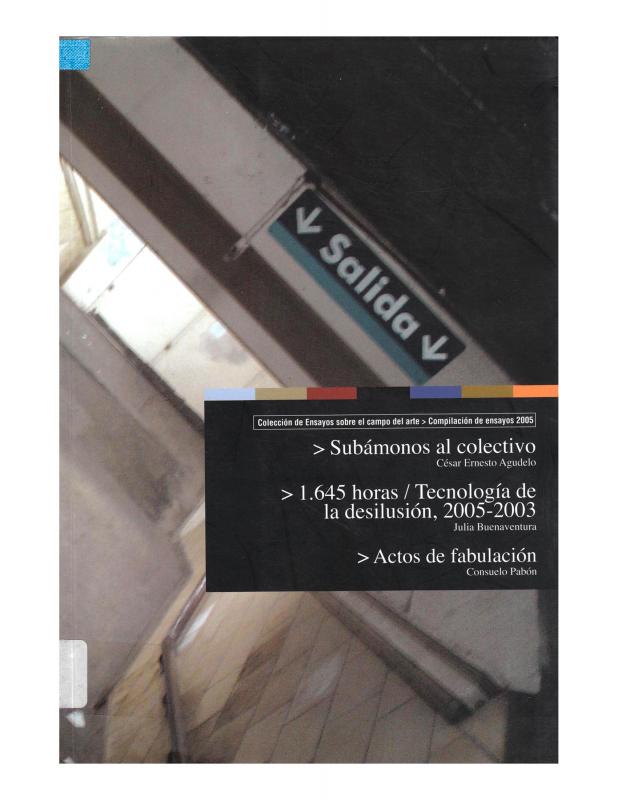

This text points out the paucity of historical and theoretical documentation on the body and performance art in the Colombian art scene, even though starting in the eighties, that genre grew increasingly important. The article provides a reading of works by several Colombian artists, among them Constanza Camelo (b. 1970), Raúl Naranjo (b. 1968), Erika Mabel Jaramillo (b. 1974), Fernando Pertuz (b. 1968), María José Arjona (b. 1983), and Wilson Díaz (b. 1963). By the time these contemporary artists emerged, the performance genre was well established and institutionalized within the Colombian art scene owing to widely recognized older artists active in the eighties, such as María Teresa Hincapié (1954–2008), Rolf Abderhalden (b. 1956), Alfonso Suárez (b. 1952), and many others. Arcos Palmas discusses specifically the research, and exhibition, Actos de Fabulación (2000) [see doc. no. 1099666, doc. no. 1099681, doc. no. 1129442, and doc. no. 1129458], organized by curator Consuelo Pabón (b. 1961), a pioneering curatorial project that gathered theoretical material on performance in Colombia. Although that project points out major artists working in the performance genre in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, it attests to the lack of theoretical and investigative work on performance art in Colombia.

Arcos Palma argues that although the generation he discusses has received international acclaim, it has been completely ignored on the Colombian art scene. This is paradoxical since these artists are now active on the Colombian art scene: their works have received recognition at an array of events and many of them have played important roles at educational and artistic institutions. While it is clear that the object of the author’s criticism is the lack of sound discourse and thorough research on performance in Colombia, his generational reading runs the risk of imposing a univocal sociopolitical vision that minimizes the differences between the practices of artists active at that time. He therefore leaves out artists whose work is not concerned with the issues he discusses. This criticism in no way overlooks the political context in which the artists Arcos Palma does mention produced their work, nor does it ignore Arcos Palma’s insistence that this text is just a preface to later research that attempts to remedy the reigning neglect of the history of performance art in Colombia. Arcos Palma dedicates a good part of this article to descriptions of artwork, and to defining two discrete tendencies:works that involve political activism and those that entail a ritualistic or metaphysical vision.

An art critic, Ricardo Arcos Palmas (b. 1968) studied philosophy. He holds a doctorate in the sciences of art and a master’s degree in aesthetics from the Sorbonne University in Paris. He is currently (2009) the director of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia Art Museum and a professor of art history and theory at that same institution.