As expressed in the manifesto of the Neo-Concrete movement issued in 1959, the tie between life and art was a sine qua non of the work of that movement’s most radical members, that is, Hélio Oiticica and the artists known as the two Lygias (Lygia Clark and Lygia Pape). For Oiticica, the passage from the observer’s “simple and structural,” that is passive participation to an active or “sensorial” role meant orienting art to daily life, guiding former viewers toward the exercise of freedom. In Cosmococas (1970–73), the artist’s joint projects with filmmaker Neville D’Almeida, Oiticica places emphasis on drugs. In his view, any attempt the individual makes to pursue his own form of expression should be considered “art.” That experimental undertaking and deep pursuit of knowledge produces in Oiticica’s view “the suprasensorial,” or that which lies beyond the senses (see Oiticica’s text “Aparecimento do suprasensorial na arte brasileira” [doc. no. 1110620]).

Hélio Oiticica (1937–80) was a Brazilian Neo-Concrete artist. After studying painting with Ivan Serpa at the Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro in 1954, he joined the Grupo Frente and the Neo-Concrete movement. In addition to the geometric paintings he worked on while studying with Serpa and as a member of the Grupo Frente, Oiticica did performances and participatory works. His Parangolés (1964)—capes made with fabric and recycled materials—were used for performances at the Escuela de Samba Mangueira. Oiticica also created enveloping spaces like Nucleus (1959–60), an environment constructed with hanging and painted strips of wood based on Piet Mondrian’s Constructivist ideas. In 1967, he made the environment Tropicália at MAM-Rio. Tropicália was an installation of rooms with plants and materials (water, sand and stones, as well as a parrot, a television set, and other elements from Brazilian popular culture), that is, an environment designed to stimulate the senses. He applied the same principles for Eden, an environment made in 1969 at the Whitechapel Gallery in London. The name “Tropicália” was later used by Brazilian musicians to refer to a new style of music that brought together international pop and traditional Brazilian music. The word, which came to form part of Brazilian popular culture, is applied to something Brazilian in nature. In 1970, Oiticica took part in the group show Information held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

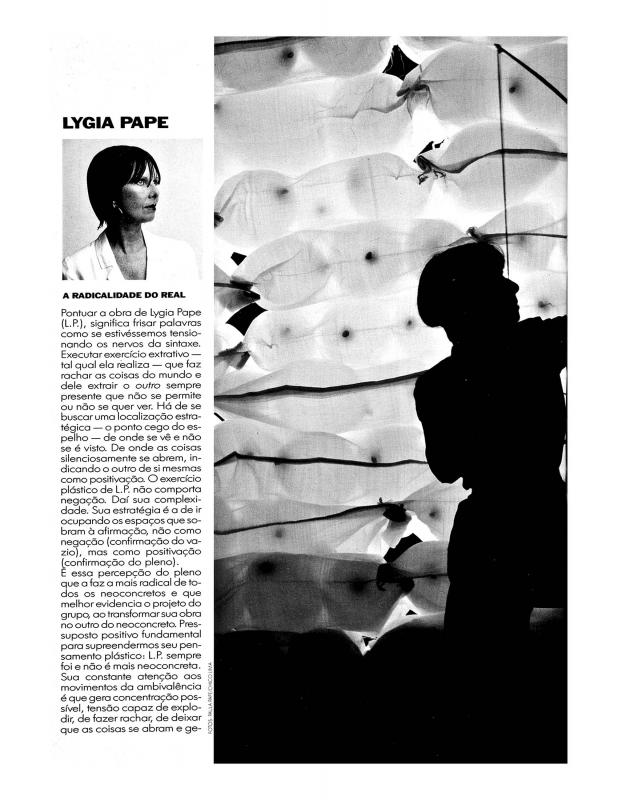

Artist Lygia Pape (1927–2004) skillfully worked in a number of areas: sculpture, printmaking (Livro-poema, 1960), dance (Ballet neoconcreto, 1960), and film (O guarda-chuva vermelho [The Red Umbrella, 1971]). She first studied art with Ivan Serpa in the Rio de Janeiro-based Grupo Frente (1955). Having participated in the Neo-Concrete movement from the time its manifesto was published in the Jornal do Brasil (March, 1959), Pape was an emblematic figure in that movement. She developed radical works and projects throughout the sixties—videos and installations that satirized the military dictatorship in power from 1964 to 1985—and into later decades as well. The metaphors in her work from the eighties—the decade of the somatic apologia—were more subtle, as her art became a vehicle for bodily and vital experiences of an existential, sensorial, and psychological nature. Geometry (the Concrete legacy) was what structured all of her later work. Her efforts always wavered between a highly intellectual approach and physical participation on the part of an active viewer. Her most striking works include Tecelares and thetrilogy Livro da Criação/ Livro da Arquitetura / Livro do Tempo, and TtEias [Spider Web, 1979].

Hélio Oiticica analyzes Lygia Pape’s artistic development, which in his view, begins to venture into space starting with her Livro da Criação, produced in 1960 [doc. no. 1110628].

In “Lygia Pape: a radicalidade do real” [doc. no. 1111257], art critic Márcio Doctors, who considers Pape the most radical of all the Neo-Concrete artists (including Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica), observes that her work empties out the borders between “the inside ” and “the outside.”