This essay was written in 1969, but was not published until 1975, when it appeared in the folder presented at 40 gravuras neoconcretas, the exhibition of prints by Lygia Pape, at the Maison de France gallery in Rio de Janeiro. This was the artist’s first solo exhibition, strange as that may seem considering the creative and experimental experience she accumulated from her earliest works until the late 1950s.

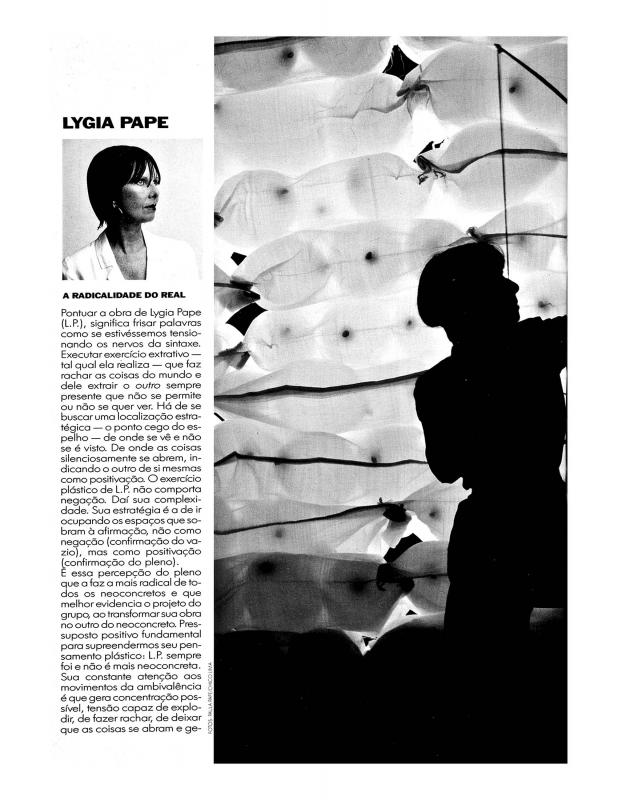

Lygia Pape (1927–2004) worked skillfully in several areas: sculpture, prints (Livro-poema, 1960), dance (Ballet neoconcreto, 1960), and film (O guarda-chuva vermelho [The Red Umbrella, 1971]). She first studied the visual arts under Ivan Serpa in the Grupo Frente in Rio de Janeiro (1955). She was a member of the neo-Concrete movement ever since the publication of its manifesto in the Jornal do Brasil (March, 1959), and became a regular participant in the group’s radical projects throughout the 1960s—when she produced satirical videos and installations about the military dictatorship (1964–85)—and for many decades after that. Her metaphors were more nuanced in the 1980s—the somatic apologia decade—when her work became a vehicle for physical, vital experiences at an existential, sensory, and psychological level. Geometry (the legacy of concrete art) never ceased to be a central part of her later works; her ideas always fluctuated between a highly intellectual approach and the physical participation of a sort of actively involved viewer. Her most notable works include: Tecelares and her trilogy Livro da criação/ Livro do tempo/ Livro da arquitetura and, subsequently, TtEias [Spider Webs, 1979].

Hélio Oiticica (1937–80) was a Brazilian Neo-Concrete artist. He started studying painting with Ivan Serpa in 1954 at the Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro. He later joined the Grupo Frente and the Neo-Concrete movement. In addition to his geometric paintings, which he worked on while he was studying with Serpa and was a member of the Grupo Frente, Oiticica produced performance and participatory art. His Parangolés (1964)—capes made with fabrics and recycled materials—were worn by the Mangueira Samba School during their performances. Oiticica also created immersive spaces, such as Nucleus (1959–60), which was an installation constructed from suspended painted wooden slats inspired by the Constructivism of Piet Mondrian. In 1967 Oiticica created the immersive environment Tropicália at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro. Tropicália was an installation consisting of rooms with plants and materials such as water, sand and stones, a parrot, a television set, and various other elements that were representative of Brazilian popular culture. The environment was designed to promote sensory stimulation. Oiticica applied the same principles to Eden, the installation he created in 1969 at the Whitechapel Gallery in London. The name Tropicália was used by Brazilian musicians to describe a new style that combined international music and pop with traditional Brazilian music. The term “Tropicália” was absorbed into popular Brazilian culture and came to signify a uniquely Brazilian essence. In 1970 Oiticica took part in the group exhibition Information at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

In “Lygia Pape: a radicalidade do real” [see doc. no. 1111257], the art critic Márcio Doctors reviews the work produced by this artist—whom he considers to be the most radical of the neo-Concrete artists (including Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica, among others)—in which he detects a purging of the boundaries between “what is inside” and “what is outside”.

Regarding the event that took place in Rio de Janeiro in 1968, Oiticica and Rogério Duarte jointly wrote “Apocalipopótese no Pavilhão Japonês” [doc. no. 1110621]. Oiticica also wrote a review of the event at a later date, when he was in London: “Apocalipopótese” [doc. no. 1110682].