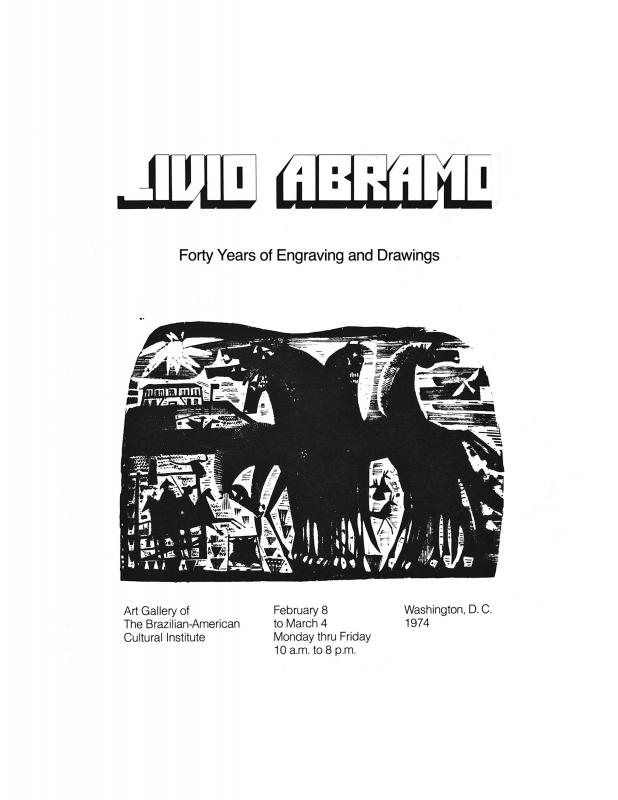

With a brief historical sketch of wood engraving, “the most authentic medium within the visual languages,” the author establishes connections between expressionist art —such as the Brücke [Bridges], Blaue Reiter [Blue Rider], and Sturm [Storm] groups—and, in the Brazilian context, Lasar Segall, who is in the author’s judgment the most complete Brazilian artist and draftsman, in addition to the most renowned artists within the resurgence of engraving in the 20th century: Oswaldo Goeldi and Lívio Abramo. Abramo laid the foundation for a type of edging that produces furrows in wood capable of shaping light in order create refined forms. In his text, Geraldo Ferraz compares Lívio the journalist (mediocre) and Lívio the engraver [who was attentive to current events in his implacable criticism of the Nazis, Fascists and the “nationalists” who opposed the Spanish Republic (1936?39)]. Initially classified among the “suburban artists and painters” (proposed by Mário de Andrade), Abramo favored São Paulo’s outlying areas and its way of life, combining them with simple graphics and a plain aesthetic, thus juxtaposing his graphic language with his social commentaries. He is more concerned with methods of survival than with a particular political-ideological posture. The author [Ferraz] was interested in the use of engravings in publications, highlighting Goeldi and Leskoschek’s illustrations for the complete works of Fyodor Dostoyevsky published by José Olympio Editora; and Abramo’s 27 xylographs for the book Pelo Sertão [Through the Northeastern Region] by Afonso Arinos. Finally, the author contrasts the “Gothic” touch of Flemish artist Frans Masereel and Lívio’s “Mediterranean” style, owed in particular to the “Greek and Pompeian reverberations” that emanate from his series of drawings on Santeria in “Macumba”.