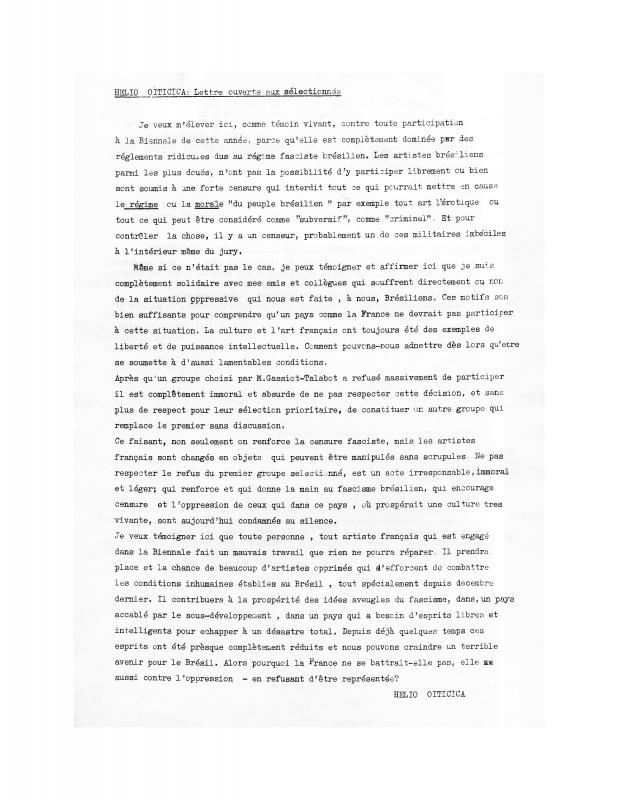

This interview was included in the book Patrulhas ideológicas (marca reg.)-Arte e engajamento em dabate. Edited by Carlos Alberto Pereira and Heloísa Buarque de Hollanda (1979–80), the book provides the testimonials of around twenty Brazilian artists and intellectuals on the themes of politics and culture. The “function” of the artist under a repressive political regime was the central theme of the collection, and the background of this edition was the slogan of the military dictatorship (1964–81): “relaxation that is slow, gradual, and secure.” Among other opinions, the book included those of the film director Glauber Rocha, the philosopher José Arthur Gianotti, the singer/songwriter Caetano Veloso, and the artist Lygia Clark. After the interview, Hélio Oiticica sent an addendum saying that the theme of “thought police” was unpleasant, and that he did not believe in a “pseudo-political/cultural function” for artwork. In the interview, he emphasizes his boredom with the tracts printed in pamphlets and the populist outlook that have tried to link these activities, whether issued by artists or politicians or by the left or right wing. Hélio Oiticica (1937–1980) was a Brazilian artist practicing Neo-Concrete art. Oiticica began to study painting with Iván Serpa in 1954 at the Museo de Arte Moderno do Río de Janeiro and later became a member of both the Grupo Frente and the Neo-Concrete movement. In addition to the geometric paintings he executed during his time with Serpa and as a member of Frente, Oiticica created performances and works of participatory art. His Parangolés (1964)—layers made of fabric and recycled materials—were used for performances at the Escuela de Samba Mangueira. Oiticica also created spaces to surround the viewer, such as Núcleus (1959–60), an environment constructed with strips of painted wood and hangings rendered based on the ideas of Piet Mondrian about Constructivist art. In 1967, he created the environment Tropicália at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Río de Janeiro. Tropicália was an installation of rooms with plants and materials such as water, sand, and stones, as well as a parrot, a television, and other elements of popular Brazilian culture. It was an environment designed to stimulate the senses. He also applied the same principles to Edén, another environment created by Oiticica in 1969 in the Whitechapel Gallery in London. The name Tropicália was taken by Brazilian musicians (MPB) to denote a new style of music that mixed international music and pop with traditional Brazilian music. The term “Tropicália” then came to be part of Brazilian popular culture, meaning that the event described had a Brazilian national stamp. In 1970, Oiticica participated in the group show Information at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. [As supplementary reading, see the following texts by Oiticica in the ICAA digital archive: “Aparecimento do suprasensorial na arte brasileira” (doc. no. 1110620); “Apocalipopótese” (doc. no. 1110682); (untitled) [“Apocalipopótese no Pavilhão Japonês (…)”] (doc. no. 1110621); “Brasil diarréia” (doc. no. 1090409); (untitled) [“Cada vez que procuro situar (…)”] (doc. no. 1110352); “Côr, tempo e estrutura” (doc. no. 1110353); “Declaração de princípios básicos da vanguarda” (doc. no. 1110371); “Esquema geral da nova objetividade” (doc. no. 1110372); “Helio Oiticica : lettre ouverte aux sélectionnés” (doc. no. 774506); among others].