[This is a] text introducing the TLA written by the Venezuelan art critic Rafael Pineda (b. 1926).

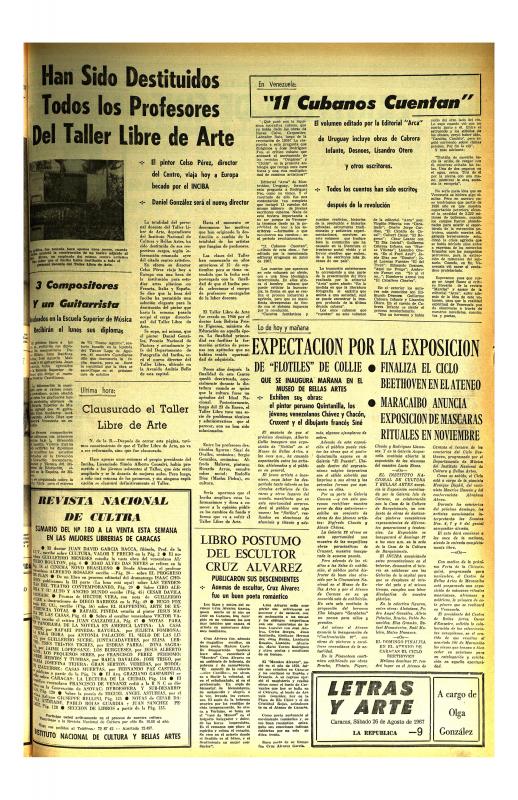

This was the first group exhibition held by the Taller Libre de Arte (TLA) at the Liceo Andrés Bello de Caracas, which opened in May. Previously, the members of the TLA had presented a significant number of exhibitions at educational centers such as: Liceo Fermín Toro (a total of three); Escuela Normal Gran Colombia; and the Escuela Federal Rafael Acevedo (a total of two). The decision to form the TLA emerged at the Liceo Fermín Toro, based on discussions that took place there between young artists of La Barraca de Maripérez, painters who were Social Realists, and students of the Escuela de Artes Plásticas y Aplicadas. It is important to be aware of the expectations instilled in the young artists by the members of the TLA, who were for the most part highly conflicted and agitated in the midst of the national political scene. To TLA members, the hopes for confronting this situation were based on fostering an innovative, aesthetic, avant-garde subversion—with surreptitious political and ideological connotations. These hopes were closely bound up with student artists. The catalogue-preface writer Rafael Pineda was one of those intellectuals who contributed to the first issue of the journal Taller, issued by the TLA in June 1950. Pineda’s preface takes the tone of a harangue that seeks to firmly establish a spirit of unity in diversity; freedom; emphasis on local, contemporary art; and a universality that the workshop members had already adopted. In fact, by midyear 1949: “(…) the Taller Libre de Arte was winding down the Cubist experience inherited from the school, and as if by force of circumstance, was obligated to propose new alternatives, determine other directions, and define its own place in art history.” [See Francisco Da Antonio, Textos sobre arte (Caracas: Fundación Editorial El Perro y la Rana, 2007), p. 270]. Abstract art was in common practice among the various TLA members at the time (including Alejandro Otero and Omar Carreño). The sources of Afro-American, Pre-Hispanic, and magical/religious culture as well as references to popular and telluric painting had all obtained acceptance and awards at the official salons (with artists such as Mario Abreu, Oswaldo Vigas, and Humberto Jaimes Sánchez). Moreover, the association of such artists with Los Disidentes (Paris, 1950) was also evidently well known. This being the case, Pineda’s preface takes an urgent tone that may reflect his own concern that the TLA was starting to lose its grip. In fact, in July of that year, Régulo Pérez reported a crisis at the Taller Libre de Arte, so called by El Nacional in its published report of August 25. By then, the TLA was under the direction of Louis Rawlinson, following the departure of Alirio Oramas to France, in a change of administration that was seriously questioned by Oramas’s colleagues.

[For more texts on the TLA, see the ICAA digital archive: the preface, “Texto presentación,” written by Bernardo Chataing for the first group exhibition of the TLA (doc. no. 1101666); the preface, “Exposición de cuadros abstractos 1948: El movimiento moderno de abstracción-invención–concreción,” in which the TLA collective states its interest in invention and creative freedom (doc. no. 1101635); and the article, though rife with inconsistencies, informing us of the disappearance of the TLA and its replacement by another institution, the INCIBLA, “Han sido destituidos todos los profesores del Taller Libre de Arte” (doc. no. 1172267)].