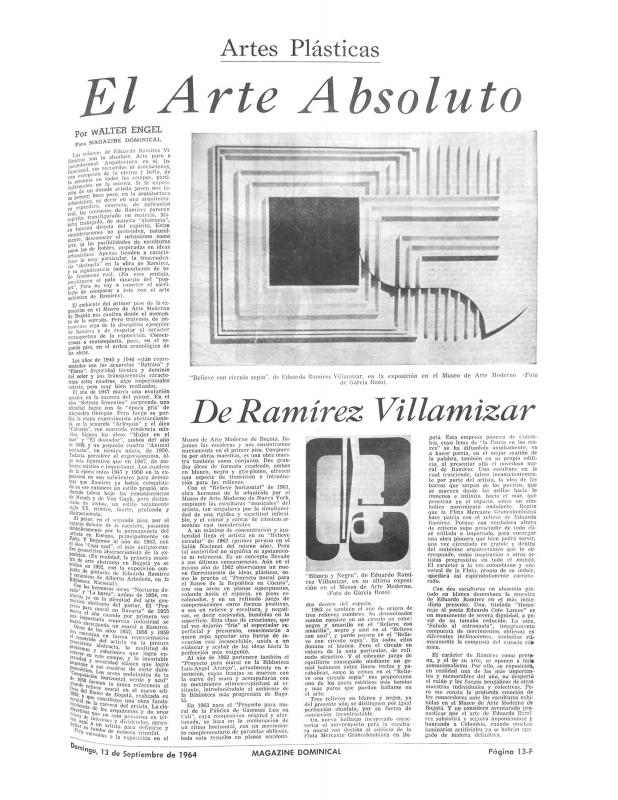

“La Catedral y el Arzobispo” by Eduardo Ramírez Villamizar (1922–2004) is essential to understanding this artist’s production as well as his relationship to art. Ramírez Villamizar is considered a pioneer of abstraction in Colombia. Many important articles on his work published in the mid-twentieth century support this assessment, among them “El Arte Clásico de Eduardo Ramírez Villamizar” [doc. no. 1093722] by Casimiro Eiger; “Un Poder Ordenador” [doc. no. 1093674] by Marta Traba; and “El Arte Absoluto de Ramírez Villamizar” [doc. no. 1093770] by Walter Engel. His work is considered self-referential, pure, and removed from any external reference; it is seen as totally rational and focused exclusively on the matter of form. Insofar as “La Catedral y el Arzobispo,” written by Ramírez Villamizar himself, affirms that he had a close relationship with religion and the Catholic Church, it pointedly questions the vision formulated by these major art critics.

Significantly, Ramírez Villamizar’s descriptions of iconography, temples, events, and religious celebrations in this text focus on their formal and material aspects. Clearly, his relationship with religion had a major influence on his relationship to images in general and took shape through the aesthetic of the Catholic Church. Throughout his life, Ramírez Villamizar collected religious art and objects that he used to decorate the places in which he lived. His production includes works with religious themes, such as the paintings: Crucifixión [Crucifixion] (1950), Adán [Adam] (1945), Cáliz y hostia [Chalice and Host] (1960), and Lucha entre Jacob y el Ángel [Struggle Between Jacob and the Angel](1947); and the drawings: Monjas muertas [Deceased Sisters] (1983), Ángeles [Angels] (1980), and Paraíso perdido [Paradise Lost] (2004); and the sculptures: Custodia (1980), Custodia Homenaje (1983), Catedral policromada [Polychrome Cathedral] (1979), and Brazo de santo [Arm of the Saint] (1963). On the basis of this text as well as some of Ramírez Villamizar’s artwork, it can be argued that at least some of his production is in fact referential, and influenced by concerns beyond the specific realm of art.