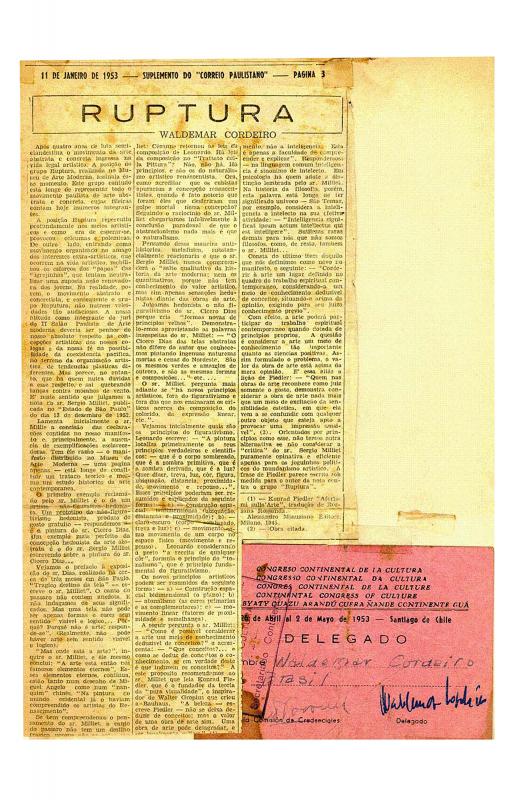

This article reveals the programmatic nature of the Brazilian Concrete art movement, which brought together a variety of artists working in literature, the visual arts, music, and industrial design. Influenced by Novacap’s urban planning strategies (Brasilia, 1961), the pilot plan for concrete poetry was based on a theoretical synthesis of the texts published thus far by the poets Augusto de Campos (b. 1931), Haroldo de Campos (1929–2003), and Décio Pignatari (1927–2012). In 1952—as a tribute to a Provençal poet, Arnaut Daniel, mentioned by Ezra Pound— these three poets started the Grupo Noigandres in order to establish and communicate the objectives of concrete poetry in São Paulo. During the following ten years (1952–62) they published five issues of the magazine of the same name. The members of the Grupo Noigandres were in close contact with the intellectuals, painters, and sculptors who joined forces in São Paulo in 1952 to form the Ruptura group—see the “manifiesto ruptura” published in O Estado de S. Paulo [doc. no. 1085337]. This group of visual artists coalesced under the leadership of Waldemar Cordeiro (Rome, 1925; São Paulo, 1973) who had emerged as one of the main theoreticians of local postwar movements since his arrival in Brazil in 1947.

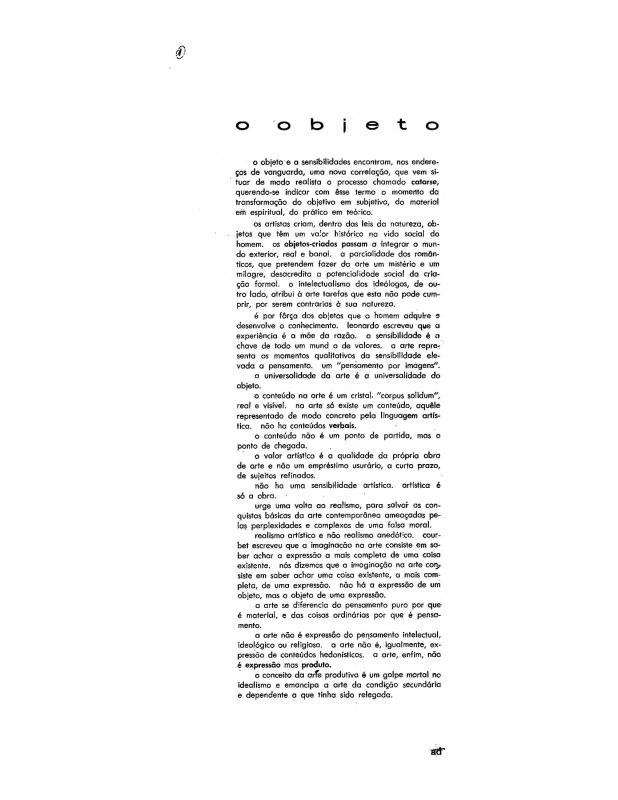

Several of the plano-piloto’s proposals for concrete poetry were reminiscent of, and similar to, some of the ideas that Cordeiro had expressed earlier in articles published in Brazilian magazines (specifically in two architectural journals, A&D and HABITAT) since the late 1940s. Plano-piloto agreed with Cordeiro on his key points: the defense of the autonomy of language, a firm opposition to subjective expression, and the idea that the poem (or painting) is a product (or object). Cordeiro’s seminal essay, “O objeto”—published in A&D magazine, 20 (1956)—posits that “The work of art is not an expression, it is a product whose contents are its own essential artistic elements,” a theory with which the Grupo Noigrandres agreed [see doc. no. 1086891].

In concrete poetry, “the word” is considered a sign that is independent of its referent, just as lines, colors, and forms in Concrete art are autonomous visual elements that are never subordinate to any kind of illustration associated with the world of appearances. In both cases, the work of art refers only to itself, as stated by one of the theoreticians of concrete poetry, the German philosopher Max Bense, who worked in the fields of logic, aesthetics, and semiotics: “Alles Konkrete ist hingegen nur es selbst.”