Kilka Wawa, or “Child Writing” was a project organized by the Colombian Antonio Caro Lopera (b. 1950) among the children of the Inga community. The artist’s goal was to create a reading and writing primer that would help to avert the extinction of this indigenous language, a Quechua dialect spoken by certain communities living in southern Colombia.

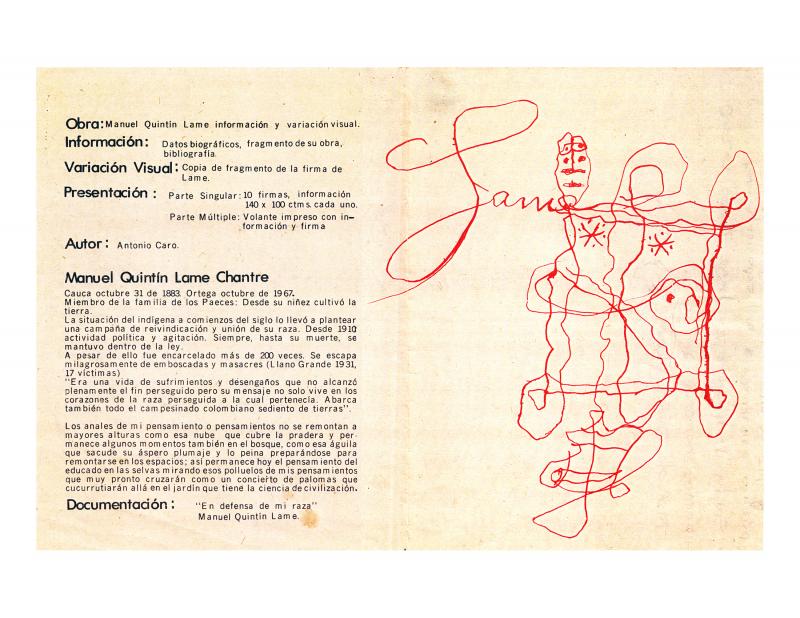

Kilka Wawa is an integral part of the works that Caro produced on the subject of Colombian reality and identity, that included his repeated use of the corn plant to refer to indigenous traditions; the reddish dyes of the achiote (Bixa Orellana) [annatto] used in the print Onoto (1999) as a poetic reference to the land; and the use of the signature of the leader Manuel Quintín Lame to allude to conflicts over land ownership and indigenous politics [see “Manuel Quintín Lame información y variación visual” [Manuel Quintín Lame Information and Visual Variation], doc. no. 1082735].

This text is not merely the only existing critical review of this exhibition; when Parra questions the appropriateness of awarding a graphic prize to a person who lacks the sort of training (pedagogical, speech-language pathology, psychological, and the like) that a project of this nature requires, he highlights the difficulty involved in judging the work of artists like Caro, and draws attention to the fact that the prize makes negligible contributions to the graphic arts in the country. Such artists, who focus on Conceptual, social, and political art, establish connections—in their practice and their theory—with other disciplines (design, sociology, gastronomy, and so on).

Among Colombian artists who showed an interest in the culture of indigenous groups, we should consider the nationalist approach of Luis Alberto Acuña (1904–1984) and Rómulo Rozo (1899–1964), both of whom belonged to the Bachué movement in the 1930s. More recently, we should consider the work of Nadín Ospina (b. 1960) on cultural simulations and hybridizations.