The combative painter, designer, landscape painter, art critic, and theoretician Waldemar Cordeiro (1925–73) outlines his ideas on theory and practice in the field of art and technological advances. After being part of the Ruptura concrete art group (1952) in the 1950s, and creating his semantic objects—or “Popcretos”—in the 1960s, he continued with his artistic experiments. With the help of, for example, the German thinker Max Bense, the “Pop” concept led him to a dialectical approach that fluctuated between “things” and “realities.” Cordeiro is convinced that contemporary art relies on an objective language that presents things (or semantic items) that have nothing to do with illustration, which he calls “semantic concrete art.” He discusses this idea, and others, in his essay published in HABITAT, the architectural magazine: “Novas tendências e nova figuração” [doc. no. 1110840].

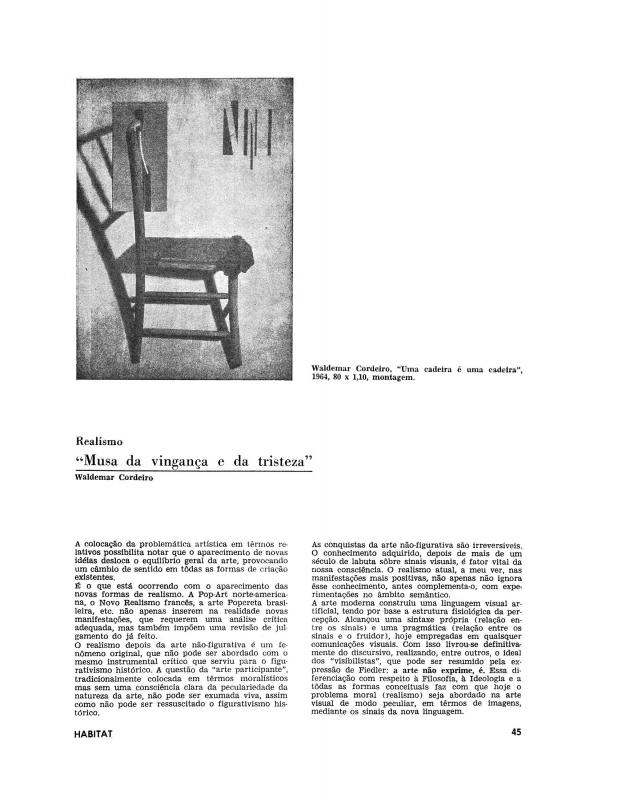

The concept of “current realism under a critical action” referred to by Cordeiro echoes some of the themes in his important earlier writings, such as “[Produto direto de uma atitude crítica]” [doc. no. 1087239], which was written for an exhibition of his works in Campinas (1960). On the other hand, this document should be interpreted in terms of a greater development that he writes about under the title of “Realismo: ‘musa da vingança e da tristeza’” [doc. no. 1110839]. The reality that Cordeiro is referring to is of a technological nature, which is why, since the previous decade, in the 1950s, he began to use mathematical concepts and geometrical forms in his visual art.

This is an article by the top physics theoretician in Brazil, the politician and art critic Mário Schenberg (1914–90), who usually published scientific articles on thermodynamics, quantum and statistical physics, astrophysics, and mathematics. He was president of the Brazilian Physics Society (1979–81) and Director of the Physics Department at USP (1953–61). He served two terms as a congressman for the state of São Paulo. His association with the PCB (Brazilian Communist Party) had a devastating effect on his life after the military coup in 1964, when he was stripped of all his political, academic, and personal rights. His article about Cordeiro, written prior to the fascist putsch, explored the unconventional subject of artistic schools, trends, and movements.

Cordeiro actually began painting his series of irregular shapes and forms in the early 1960s. So, when Schenberg compared Cordeiro’s paintings to Wassily Kandinsky’s work and drew attention to Cordeiro’s free use of color, Schenberg was identifying the very characteristics that Cordeiro had once criticized in other concrete works of art. Schenberg is mistaken, however, when he uses the term “neo-concrete” to refer to that particular phase of Cordeiro’s work and to artists in both São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, since that misrepresents the radical split between those two groups, a division that, to this day defines art criticism in Brazil.