In this article, the Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre (1900–1987) reviews the work of Candido Portinar through a prism of regional ethnic unity and diversity. Freyre’s views of society are of a distinctly “comprehensive” nature. Even when works of art reflect social class conflicts, as in Portinari’s paintings, the sociologist puts a positive spin on them by pointing out the “benefits of miscegenation,” therefore avoiding a sociopolitical discourse that could sully his aristocratic pedigree.

Gilberto Freyre was one of his country’s most influential thinkers, particularly in terms of race, during the first half of the twentieth century. In 1993, he gained international recognition for his great work Casa-Grande & Senzala, the first book in a trilogy that also included Sobrados e mucambos (1938), and finally, Ordem e Progresso (1957). The trilogy is a study of races and cultures in Brazil since the colonial period and their evolution into a “racial democracy.” Freyre therefore ponders the Afro-Brazilian heritage and describes Brazil in terms of its conciliatory nature. Other Latin American writers have addressed this same idea, such as the Mexican José Vasconcelos in his La raza cósmica [The Cosmic Race] in 1926, and the Cuban anthropologist Fernando Ortiz in Contrapunteo cubano de tabaco y azúcar [Cuban Counterpoint: Tobacco and Sugar] in 1940. Freyre’s version of these narratives introduces the idea of “lusotropicalismo” [Portuguese Tropicalism], a theory that posits miscegenation as a positive force in Brazil’s development. In Freyre’s opinion this is reflected in terms of inter-American relations and the search for unifying categories based on sociocultural factors [on this subject, see the ICAA digital archive, “Interamericanismo” (doc. no. 807911) and “A propósito da política cultural do Brasil na América”(doc. no. 807856), respectively].

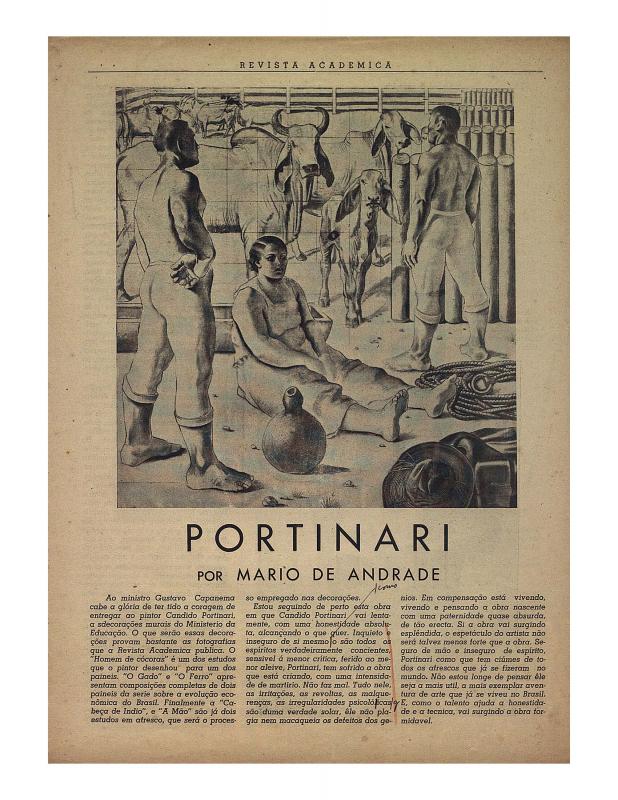

Candido Portinari (1903–1962), together with Emiliano Di Cavalcanti (1897–1976), was the official painter of Brazil from the late 1930s to the mid-1950s. He was a controversial figure in academic circles and among Brazilian supporters of abstract art. The poet and art critic Mário de Andrade wrote about Portinari’s work during that period (“Portinari,” doc. no. 781236). Portinari’s relationship with Lucio Costa led to the former’s involvement in the MES project (Ministério de Educação e Saúde, 1936–1942), the signature building in Brazilian modern architecture. To understand his tile mural for the façade of the building’s auditorium, see “A pintura mural de autoria de Cândido Portinari” (doc. no. 1110857). His political leanings prompted him to join the PCB (Partido Comunista Brasileño) during the following decade, and in 1947, he ran for a senate seat. Persecuted by Eurico Gaspar Dutra’s anticommunist government, he went into exile in Uruguay.