The artist and academic Francisco Brugnoli (b. 1935) wrote about the work of Matilde Pérez (1916–2014) in “La persistencia de lo discontinuo” on the occasion of her exhibition El ojo móvil at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes (Santiago, 1999). The exhibition, which is considered a landmark event that acknowledged her long career, was presented as part of the MNBA series Antología de artistas chilenos contemporáneos. Pérez exhibited paintings, prints, collages, and sculptures that demonstrate her far-ranging explorations beyond her early work as a painter. One example of that multidisciplinary approach is her intervention in architecture with works such as Friso cinético, which was part of the façade of the Apumanque shopping center in Santiago.

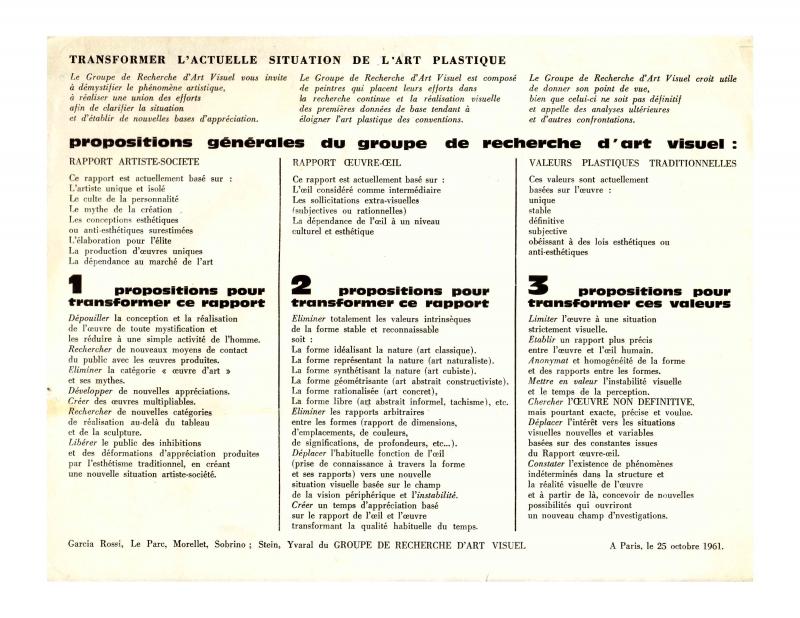

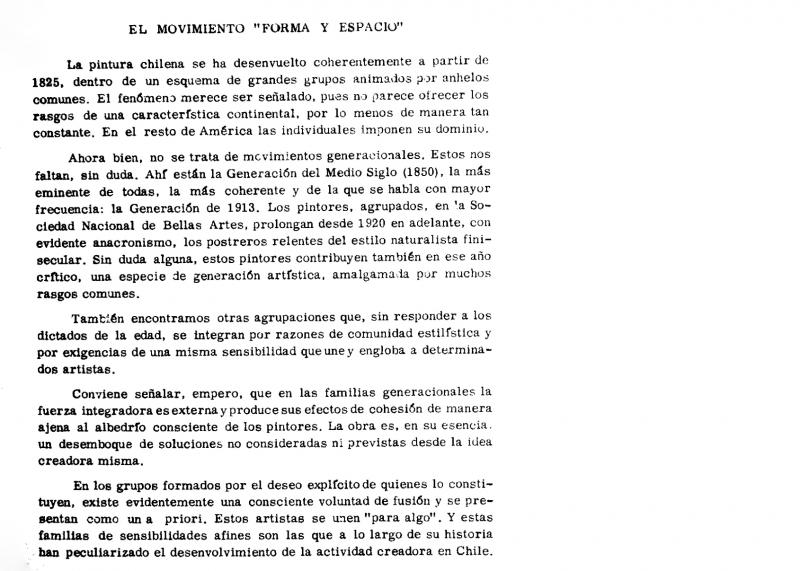

Matilde Pérez is considered a pioneer in kinetic art in Chile, though she started out working with geometric abstraction. She enrolled at the Escuela de Bellas Artes de la Universidad de Chile in 1939 and joined the teaching staff there in 1951 (she began her career as an artist in the mid-1940s). In 1955 she was a founding member of the Rectángulo group, turning away from figurative expression to focus on abstract art consisting of schematic drawings and color planes. She began exploring kinetic art and its ability to stimulate the viewer’s eye after meeting Victor Vasarely (1906–1997) and the GRAV (Group de Recherches d’Art Visuel) in the early 1960s in Paris—see (doc. no. 773122) in the ICAA Digital Archive. She and Vasarely became close friends and had a creative relationship. [On the subject of the Rectángulo group—previously known as the “Movimiento Forma y Espacio”—see: “El movimiento Forma y Espacio” (doc. no. 749831) by Antonio Romera.]

In 1970 Matilde Pérez started including electricity in her work to expand her study of movement and its sensory relationship with the viewer. Her works usually use movement to create optical illusions with color and form; they also achieve a kinetic effect through the use of light, as a result of her research into physical phenomena, including illumination and perception.

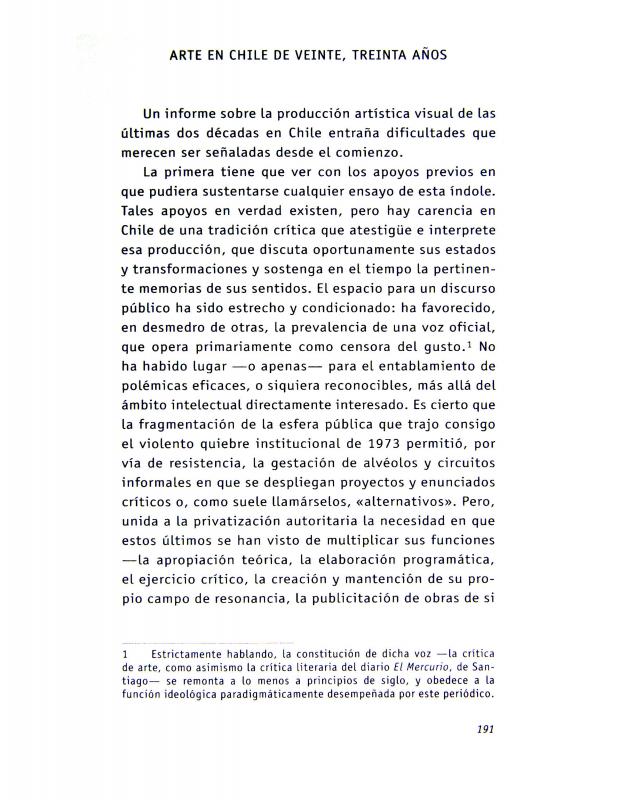

Brugnoli’s essay suggests a genealogy for Chilean art that, on the whole, points to examples of dependence on European art history. His critical perspective can be compared to “Arte en Chile de veinte, treinta años” (doc. no. 745095), a text by the intellectual Pablo Oyarzún (b. 1950), who provides an alternative view of the process of modernization of Chilean art centered on the Grupo Signo (1962).