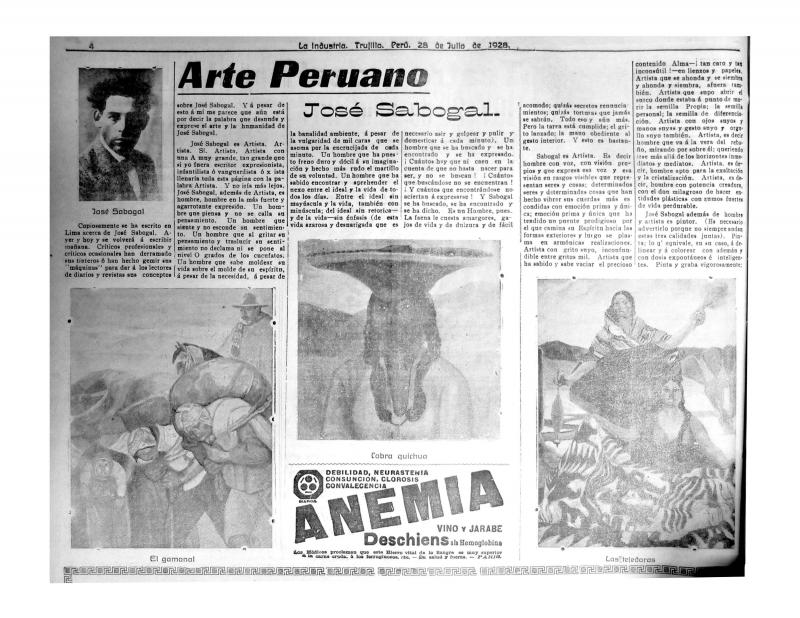

Writer and journalist José Eulogio Garrido (1888–1967) wrote this article on the work of José Sabogal (1888–1956), the founder of Peruvian pictorial Indianism, on the occasion of his visit, in 1929, to the artist’s house in Lima and to his studio at the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes (ENBA). At the end of the article, Garrido attaches another article of his authorship on Sabogal (“Arte Peruano. José Sabogal,” published in La Industria, Trujillo, July 28, 1928). [See in the ICAA digital archive (doc. no. 1140621)].

Born in Huancabamba, Piura, José Eulogio Garrido was a well-known writer and journalist who did extensive intellectual work in Trujillo. In 1910, he became the editor of the Trujillo-based newspaper La Industria, whichhe directed from 1929 to 1946. Along with outstanding young intellectuals and artists from northern Peru, such as Antenor Orrego (1892–1960), Alcides Spelucín (1895–1976), César Vallejo (1892–1938), Juan Espejo Asturrizaga (1895–1965), Macedonio de la Torre (1893–1981), Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre (1895–1979), among others, he formed part of the Grupo Norte. He edited the Trujillo-based journals El Iris (1913) and Perú (1921–22) and, from 1927 to 1929, he contributed to Amauta, a journal out of Lima coordinated by José Carlos Mariátegui. In 1949, he was named the director of the Universidad Nacional de Trujillo’s Museo Arqueológico, a post he held until 1963. Influenced by the period’s Indianist movement, Garrido’s literary work expressed his admiration for the landscapes and cultures of northern Peru. His outstanding works include the chronicles he published in La Industria and his books Visiones de Chan Chan (1931), Carbunclos (1946), and El Ande (1929 and 1949), illustrated by Camilo Blas and Sabogal. As this text—like other articles published over the course of the 1920s—evidences, Garrido was a declared admirer and friend of Sabogal.

Pictorial Indianism, which peaked in Peru in the twenties, thirties, and forties, was part of a wider movement in Peruvian society that attempted to redefine national identity in terms of native elements. While, at a certain moment, Indianism’s chief concern was the revalorization of “the indigenous” and of an Inca past seen as glorious, the movement also defended a mestizo identity that brought together “the native” and “the Hispanic.” José Sabogal was indisputably the leader and mind behind Indianism in the visual arts. His deep sense of “rootedness” was influenced by regionalist tendencies evident in art from Spain (the work of Ignacio Zuloaga [1870–1945], among others) and Argentina (Jorge Bermúdez [1883–1926], to name just one artist)—countries where Sabogal spent a number of years studying. When he returned to Peru in late 1918, he settled in Cuzco, where he produced almost forty oil paintings of local characters and views of the city that were exhibited in Lima in 1919. That exhibition is considered the formal beginning of pictorial Indianism in Peru. His second solo show in Lima—the one that enabled him to consolidate prestige—was held in the galleries of the Casino Español in 1921. In 1920, Sabogal joined the faculty of the newly founded Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes, which he then directed from 1932 to 1943. The following painters, all of whom formed part of the Indianist movement, studied at that institution: Julia Codesido, Alicia Bustamante (1905–68), Teresa Carvallo (1895–1988), Enrique Camino Brent (1909–60), and Camilo Blas (1903–85).