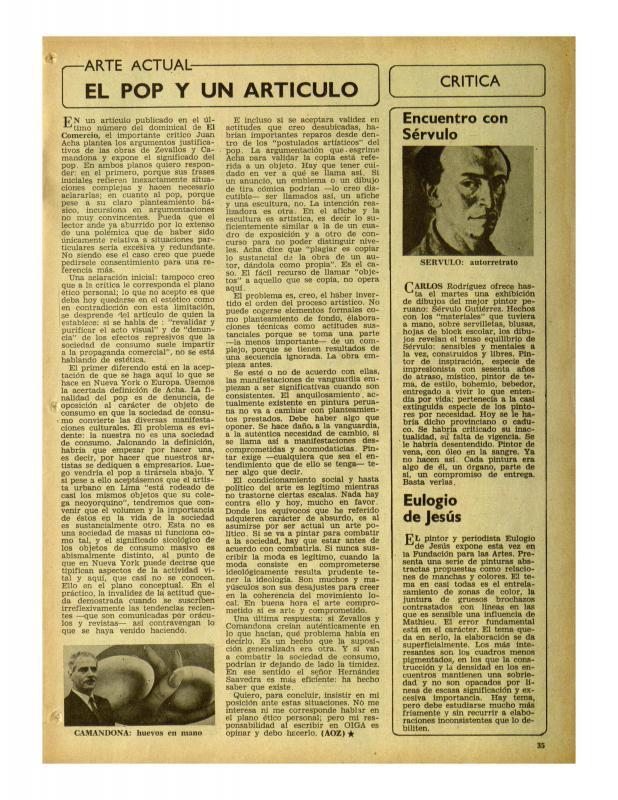

This critique is the first extensive argument to be deployed in the great debate concerning the first prize for painting that the jury awarded at the Festivales de Ancón in 1969. Speaking from what could be described as a modernist perspective, the architect and critic Augusto Ortiz de Zevallos voiced one of the most eloquent local challenges to the break with the past that Pop Art and other similar movements were advocating. He also—in another article and in a public discussion— debated with the celebrated critic Juan Acha who (as a theoretical mentor to those artistic trends) came to the artists’ defense, putting forward more recent critical and theoretical arguments on their behalf. In his current article, Ortiz de Zevallos corrects a previous opinion that was negative in terms of the competition as a whole but relatively favorable as regards Zevallos Hetzel’s work, a change of mind that can be explained by the motivating circumstances of the debate.

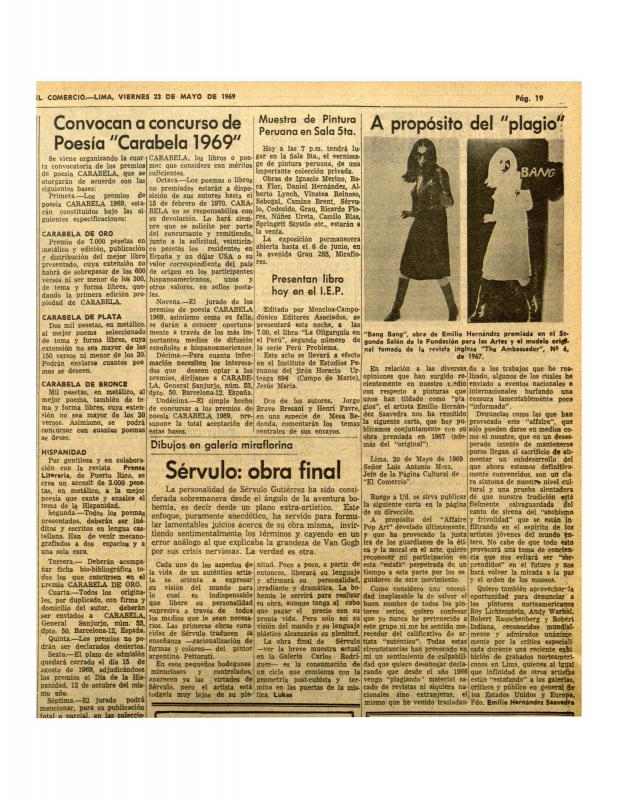

The jury’s decision concerning the first prize (for painting) at the Festivales de Ancón in 1969 was extremely controversial, and marked both the peak and the turning point for the Peruvian cosmopolitan avant-garde in the local art scene in the 1960s. At that time Ancón was the most fashionable resort on the outskirts of Lima. During the summer it hosted musical and theatrical events, as well as lectures and a painting competition which (on that occasion) attracted a great deal of attention. When the results were announced, Caretas magazine published a letter accusing the winning painting—Motociclista No. 3, by Luis Zevallos Hetzel—of plagiarism because it was a “faithful copy” of an advertisement published in the United States for a brand of motorcycles. An honorable mention at the contest went to a (playfully erotic Pop) painting by Ugo Camandona, an Italian painter and ceramicist who lived in Peru, who was also accused of supposed plagiarism. Both accusations sparked a heated debate about the value of “originality” in modern art, and about Pop Art’s role and function in consumer society. The apparent anachronism underlying the controversy clearly revealed the very limited penetration of avant-garde ideologies that had been achieved in a cultural milieu that was still reluctant to embrace the radical transformations that art was already experiencing in the rest of the world. All this was taking place in an environment that was increasingly having to adjust to the socialist and nationalist policies of the Gobierno Revolucionario de las Fuerzas Armadas (1968–75), the military regime led by General Juan Velasco Alvarado.

Luis Zevallos Hetzel, who was awarded the prize, was one of the pioneers of Pop Art in Peru, and was a member of Arte Nuevo, one of the avant-garde groups at that time. But controversial reactions and other factors subsequently led him to stop experimenting with innovative styles.

[For additional information, see the following articles in the ICAA digital archive: by Alberto Valdivia Portugal “¡Pop!” (doc. no. 1142123); by Augusto Ortiz de Zevallos “Arte Actual: El pop y un artículo” (doc. no. 1142347), and “En Ancón: significativa muestra insignificante” (doc. no. 1142364); (anonymous) “Opiniones divididas motivó el debate sobre pintor Zevallos” (doc. no. 1142269); by Emilio Hernández Saavedra “A propósito del ‘plagio’” (doc. no. 1142331); and by Luis Rey de Castro “Pintor Pop Plagia por Premio” (doc. no. 1142397)].