This essay refers to one of the exhibitions of painted boards held between 1975 and the early 1980’s at the Huamanqaqa Gallery. The author, José Sabogal Wiesse (1923−83), was an agricultural engineer. His training sparked his interest in the agrarian world and its sociocultural aspects, which he wrote about in a number of articles. He was the son of José Sabogal Diéguez (1888−1956), the founder, ideologue, and leader of the Peruvian indigenous painting movement in the first half of the twentieth century.

The Sarhua qellkas were painted wooden boards that were originally created in the Andean community of Sarhua, in the Department of Ayacucho, in the mountainous region of Central-Southern Peru, when a new house was built and the roof was put on. The godparents would give the owners of the new house a painted beam, showing the members of the family engaged in their everyday activities. The boards thus became symbols that associated the family’s genealogy with community activities and religious symbolism.

During the 1960s, however, initially due to major economic difficulties and then to the political violence affecting the area, many people from Sarhua (Sarhuinos) migrated to the city of Lima to do all kinds of jobs. In this context, two artists from Sarhua, Primitivo Evanán Poma (b. 1944) and Victor Yucra (1940-91), organized a workshop that, in 1985 became the ADAPS Association whose goal was to produce Sarhua painted boards in Lima. They had their first exhibition in 1975 at the Huamanqaqa Gallery in Lima, directed by the collector Raúl Apesteguía (1927–96). New versions of the traditional boards were exhibited, and later, in order to adapt them to an urban market, they changed the format, the materials, and the iconography, to include costumbrista motifs that reflected their local daily lives. In so doing they gave free rein to a different kind of creativity that was no longer connected to the social ritual for which the qellkas were originally produced.

The painted boards of Sarhua therefore became an example of the sort of traditional art that, due to social changes that affected its creators, evolved into a different art form. They are usually classified as “folk or popular art,” a term that has been used—often in discriminatory ways—to refer to all kinds of things that are not considered part of the official art system. This has prompted a series of important debates in the Peruvian art milieu, especially since the 1970s. See the documents relating to the controversy surrounding the retablista or altarpiece craftsman Joaquín López Antay (1897−1981).

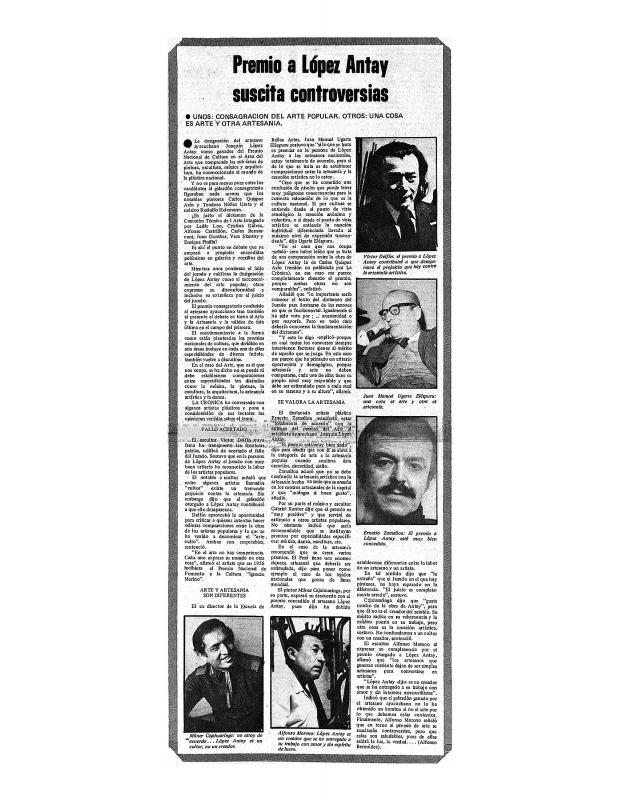

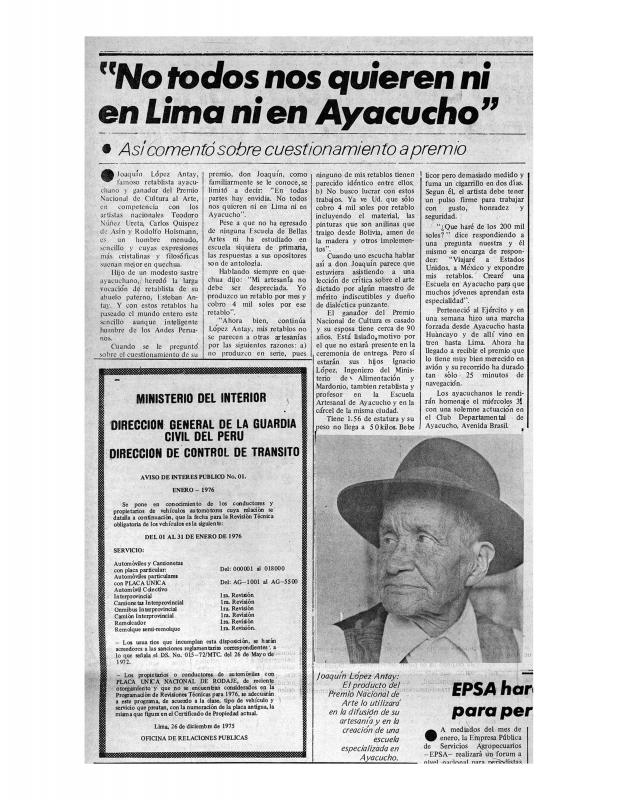

[Regarding this controversy and the ensuing debate, see the following documents in the ICAA digital archive: “Fundamentación para el dictamen por mayoría simple a favor del artista popular Joaquín López Antay” by Alfonso Castrillón, Leslie Lee, and Carlos Bernasconi (doc. no. 1135896); “Premio a López Antay suscita controversias: unos: consagración del arte popular. Otros: una cosa es arte y otra artesanía” by Alfonso Bermúdez (doc. no. 1135879); “Artistas plásticos cuestionan premio” by Francisco Abril de Vivero, Luis Cossio Marino, and Alberto Dávila (doc. no. 1135960); and “No todos nos quieren ni en Lima ni en Ayacucho’: así comentó sobre cuestionamiento a premio (…)” (no author) (doc. no. 1135930)].

[For additional reading, see the following texts in the ICAA digital archive: “Las tablas pintadas de Sarhua” by Pablo Macera (doc. no. 1140935); “Hacen Quelcas” by Nilo Espinoza Haro (doc. no. 1140967); “Las quelcas de Sarhua” by Mario Razzeto (doc. no. 1140999); and “Los pintores de Sarhua” by Félix Nakamura (doc. no. 1140950)].