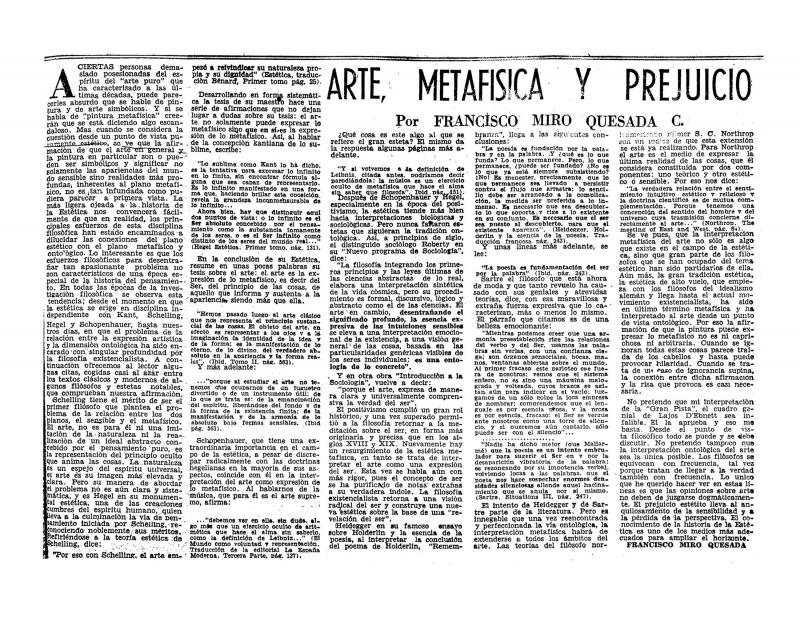

The Hungarian painter Lajos d’Ebneth (1902–82) arrived in Lima in 1949—preceded by his reputation, which was bolstered by a career that included time spent at the Bauhaus and high praise from North American art critics—and became very influential in the local art world. His international prestige, and the esoteric image that he cultivated, earned him the admiration of most Lima intellectuals. His donation of an important sculpture to the city, and the robbery of another, helped to stoke his incipient fame. In August 1950, however, he took a controversial step when he exhibited his Madonna azul, a Renaissance inspired canvas whose aesthetic merit was hotly debated by the critics. Shortly thereafter d’Ebneth showed his final piece, a work of symbolic expressionism that Francisco Miró Quesada Cantuarias (b. 1918), who was obsessed by the essential being of art, dubbed an “ontological painting” [see the following article in the ICAA digital archive, “Arte, metafísica y prejuicio” (doc. no. 1138547)]. Expanding on his elaborate praise of the Madonna, Cantuarias said that it was the crowning achievement of modern formal expression because it addressed the “expression of being.” As a result of all this, d’Ebneth’s figurative and symbolic painting was considered (by some local intellectuals) to have taken the debates between “art purists” and “social realists” to a new level, a landmark event in the country’s involvement in modern art. In response to those arguments, the writer Jorge Falcón (1908–2003)—with all the force of his communist militancy and his devotion to the indigenism of the Andes region—fiercely rejected both the Hungarian artist’s work and the critical discourse that sought to justify it [see “Meta fija de los artepuristas y metafísicos” (doc. no. 1138686)].