By defending earthly abstraction as the only legitimate option for Peruvian art, the author of this text found himself up against fellow former members of the Agrupación Espacio, a group that ostensibly rejected what it considered a partisan and totalizing view that identified “the national” with “the Andean.” In the modernist debates over this issue—debates that began in June 1951 with statements by painter Fernando de Szyszlo (b. 1925)—critic Samuel Pérez Barreto (1921–2003) defended earthly abstraction as the only possible means to devise art both “Peruvian” and modern. Despite Pérez Barreto’s position, the terms of the debate that ensued over the course of the fifties pitted “programmatic and figurative nationalism” against an “abstract” language committed solely to art. Indeed, Miró Quesada and Salazar Bondy had clashed in the debate on nationalism in art in mid-1954.

Like many intellectuals of his generation, this cultural journalist adhered to the Agrupación Espacio’s manifesto (1947), a founding document in Peruvian modern architecture and art. He was the editor of the first five issues of the journal Espacio (1949–50), that group’s platform, while also writing art criticism for the magazine Semanario Peruano. Pérez Barreto believed that it was possible to reconcile formal experimentation with a sense of historical continuity. Indeed, he maintained that the only way to create art both modern and Peruvian was by looking to the country’s earthly roots, the way pre-Columbian artists had. Well ahead of its time, Pérez Barreto’s view foretold the non-figurative veer in Peruvian painting in the sixties. Paradoxically, his position was attacked by fellow former members of Espacio during the first major polemic on abstraction unleashed in May 1951 by the statements of painter Fernando de Szyszlo.

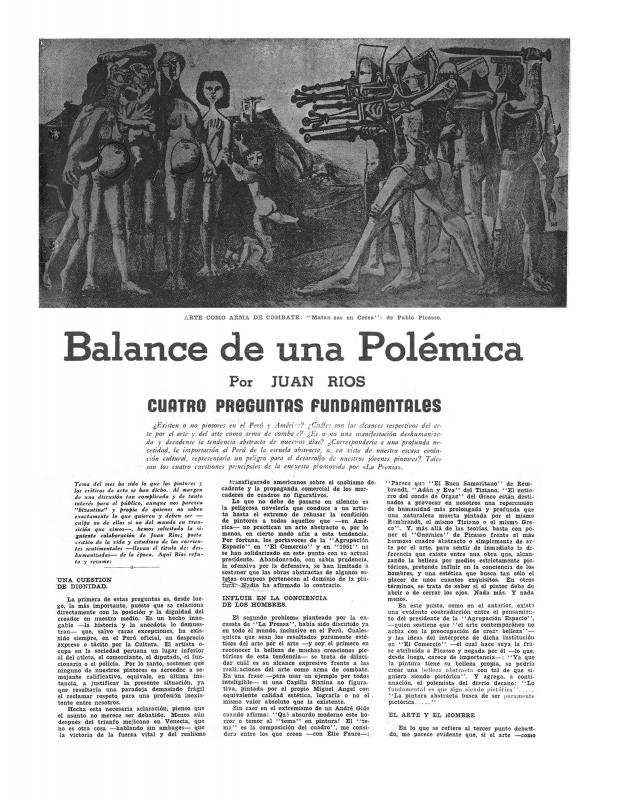

On this polemic, see “Balance de una polémica: cuatro preguntas fundamentales” (ICAA digital archive doc. no. 1137882) and “Polémica: ‘polémica Espacio’” (doc. no. 1137916), both by Juan Ríos.